Angela Dapper on gender equity, career change and designing for social impact

Angela Dapper on gender equity, landmark projects, and starting a socially focused studio - bringing big-practice skills to small community projects and finding rooms where people want to listen.

What keeps someone in architecture after decades in the profession? How do you build a career that spans landmark projects like the Stonehenge Visitor Centre, senior roles at major practices, and then step away to start a small socially focused studio? And what still needs to change for women in architecture to thrive?

Angela Dapper has navigated all of it – from stubbornly pursuing architecture in the face of early gender bias, to leading diversity initiatives at global practices, to now setting up her own socially sustainable studio in Australia.

Why architecture?

I think that question would be answered differently by every single person in architecture, and that’s the best thing about it. The field is so broad that at any one time you can be doing a completely different role. That variety is what keeps me going.

I didn’t grow up knowing any architects or anything about architecture. I grew up in a small country town. But I did know that I liked drawing – and I really liked drawing buildings. I was always drawing perspectives, elevations, for no particular reason.

I loved maths as well, and I think a lot of architects are actually quite process-driven rather than purely creative. I liked the idea of putting things together, working things out, following a process. For a long time, a career in physics or maths seemed possible.

But I decided to be an architect by the age of 12 or 13. I was really young, and I was stubborn. People would say, “You want to be an architect? You can’t do that. You’d hate it. You’re a girl.” And I thought, right – watch me.

At that point I thought it was mostly about drawing and all those lovely things. Of course, as we know, that’s only a small part of the role. But the stubbornness stayed, and that’s been a big part of my career – just holding on to what I want to do.

Gender bias and the uphill battle in the 90s…

At university in the 90s, we started out close to 50/50 men and women. By the end, the number of women had dropped to around 25%.

In my first job, I got paid less than a man who had graduated from my university in the same year with lower marks. That was a moment of, “What are you talking about?” I’m too practical to understand why that happens, but when I saw it, I hated it.

It was always in my mind – this sense that I wasn’t going to be part of an unequal profession. I wanted to do this equally. That feeling stayed with me throughout my career.

I hope it’s better now, but back then, it wasn’t a great place for young female architects in Australia or London.

Angela At the University of Adelaide in 1997.

Leaving Australia for opportunities in London

Australia always feels a little separate from the rest of the world. When you’re studying architecture there, you learn about global architecture and global architects, but you feel removed from it.

I worked in Australia for a couple of years in the 90s, doing 3D visualisations and flythroughs. At the time, no one was really doing them, so I was doing loads. It became most of what I did. I felt like that wasn’t where I wanted to be, so I took it off my CV, said I couldn’t do it, and moved to London.

When I got to London, I started doing technical detailing and felt like I was really getting into architecture. London was a place of opportunity. No one cared which university you’d been to. If you were from another country, you were taken on merit – and I loved that.

Designing the Stonehenge Visitor Centre

Stonehenge Visitor Centre, Denton Corker Marshall, 2013

It was a really difficult, complex project with a lot of interested parties. The list of stakeholders was huge – over a hundred people who were not just interested but actively involved. Every time we had a design update, we had to go back to them.

There had been so many failed schemes before ours. At one point, a prominent architect rang me up and said, “I know you’ve just won this, but it probably won’t go ahead.” I remember thinking, why are you calling me to tell me that?

The project changed locations several times. People had strong opinions. Some thought the building should be heavy and grounded because it was at Stonehenge. Barry Marshall, who designed it, had the opposite vision – something light on the landscape, the opposite of the stones themselves.

That clarity of vision held the whole project together. We designed the furniture, the materials, the structure, the sustainability – all with that in mind. When it went to site, the contractor gave a speech to the whole site team about the design vision. I’d never heard a contractor do that. And they got it. It was simple enough to stick in your head.

We weren’t just doing the visitor centre. We were also doing the roundabouts, the roads, the path around the stones, all under the same principle. Everything was low-key, nothing jarring. It all pulled together.

I spent five years on that project. It was like another child.

Under the canopy at the Stonehenge Visitor Centre by Denton Corker Marshall, 2013.

Lessons from working in three major practices

At Denton Corker Marshall in London, we were small, around 15 to 20 people, sometimes up to 50. I grew into leadership there, eventually becoming a partner. Because I’d been there so long, I knew the people, the culture, the way things worked. It was open and supportive, and I probably took that for granted.

When I became a partner, I realised I needed to learn more about leadership, so I got a coach. It was important to me to do the role well, to know the options and how other people did things.

Grimshaw was very different. 320 people when I joined. I wanted to understand what “big” looked like. In big practice, the culture has to be worked on constantly because people are always moving in and out. They had a fantastic office culture, and I got involved in it. I led the diversity group, building on the work I’d already done around gender equity.

In a big practice, you have to be open to listening. You can’t assume you know what everyone needs. And I think that’s really important in architecture. We talk a lot about long hours and low pay, but there are people doing it well, and we should talk about those examples too.

Architectus in Australia was another change. I’d applied for a role, rather than being approached. It was more prescriptive, less shaped around me. That’s when I realised I work best in places where my way of working is part of the reason they want me there.

Why Angela moved from DCM to Grimshaw

I could have stayed at DCM forever. I loved it. But when I became a partner, I thought, “I’m at the top, now what?” I was about 40, and I knew I couldn’t do the same thing for the next 25 years.

Grimshaw approached me and said they’d make a role for me to do what I did at DCM, but there. That was appealing. Being wanted for what I brought, rather than having to fit into a role, made a big difference.

Big practice has its own advantages: investment in people, courses, opportunities. It was the right move for me at the time.

Why many senior women are leaving architecture

Six months ago, I realised I didn’t want to keep putting my heart into something I didn’t believe in. A lot of senior women I know have felt the same. They’ve gone client-side, become consultants, or found other paths.

For me, it was about wanting to strip back the layers of process and hierarchy and get back to being hands-on. I wanted to take my skills and bring value to projects that really need it, social housing, community projects, where my experience could have a bigger impact than as a small cog in a big wheel.

Starting her own socially sustainable studio

What I’m looking at now is whether it’s possible to run a practice that delivers small, socially focused projects with the clarity, design quality and professionalism you usually see on much larger jobs.

I don’t think it’s right to take a profit from certain kinds of work, things that are community-based and necessary, like social housing. In my business, the aim is for profits to be rolled back into people and communities, creating a cycle where the benefits fund better outcomes for everyone.

I want to bring the value of my experience, the same level of design thinking and delivery I’ve used on high-profile projects, to clients and communities that usually can’t access it.

Listening and adapting to community clients

With these kinds of projects, you have to listen even more than usual. Clients often have very different funding structures and processes. The way the project has to be shaped is influenced by those realities.

What’s interesting is that a lot of the people leading these client organisations are similar to me. They’ve had big careers in the building industry and decided they wanted to do something more rewarding. So you’re often working with people who understand the value of good design.

But you have to fit the process to them, not the other way around. That means pausing, listening, understanding the constraints and working with them to get to a shared outcome.

And the impetus is high. These projects matter. If it’s a kindergarten, for example, it needs to be safe, have good light, be beautiful, but it also has to be affordable. You can’t just pull something from a catalogue and call it done. These are real people with real needs.

Why she started her business later in her career

If not now, when?

Covid was a turning point. It gave me and my family time to reflect on what we were doing. We’d always talked about moving back to Australia, so after Covid we decided to just do it. If we didn’t like it, we could always move back, but we wanted a different lifestyle for our kids, and it felt like the right moment.

The same thinking applied to my career. I’d always imagined going out on my own one day. At 50, I thought, I can put in a good 15 years of work on my own terms. This could be the last phase of my career, or it could evolve again. I like keeping things open.

Returning to Australia as an architect

You don’t actually have to be registered to work as an architect in Australia, but mutual recognition opened up last year, so I decided to go through the process.

That meant putting together an application and doing an interview. Basically the equivalent of the Part 3 exam in the UK. I’d been a Part 3 examiner for over a decade, so it was strange to be on the other side of the table. I took it seriously and used it as a way to refresh my knowledge, especially on the differences between the UK and Australia.

The work is very similar, but the terminology is different. I still find myself Googling things like, “What’s VAT called here?”

Culturally, there are differences too. In the UK, an architect is expected to lead the process. In Australia, clients can be more prescriptive. They’ll tell you what they want and expect you to deliver it, rather than asking for your vision. It’s a slightly different balance.

The value of panels, mentoring and professional networks

Mentoring, teaching and involvement in professional bodies have been a big part of my career. I’ve always wanted to give back, partly because I had great mentors and role models myself.

I’ve been involved with women in architecture groups, the RIBA Architects for Change diversity group, and I served on RIBA Council. Those roles introduced me to like-minded people, many of whom are still part of my network. They’re the people I call to ask what’s happening in the industry, what’s working, what’s not. It keeps you grounded.

I’ve also taught and examined at universities. Students are great. They’re optimistic, energetic, and open. I miss how involved I was in the culture of architecture in London, and I’m working on building that up again in Melbourne.

Gender equity in architecture today

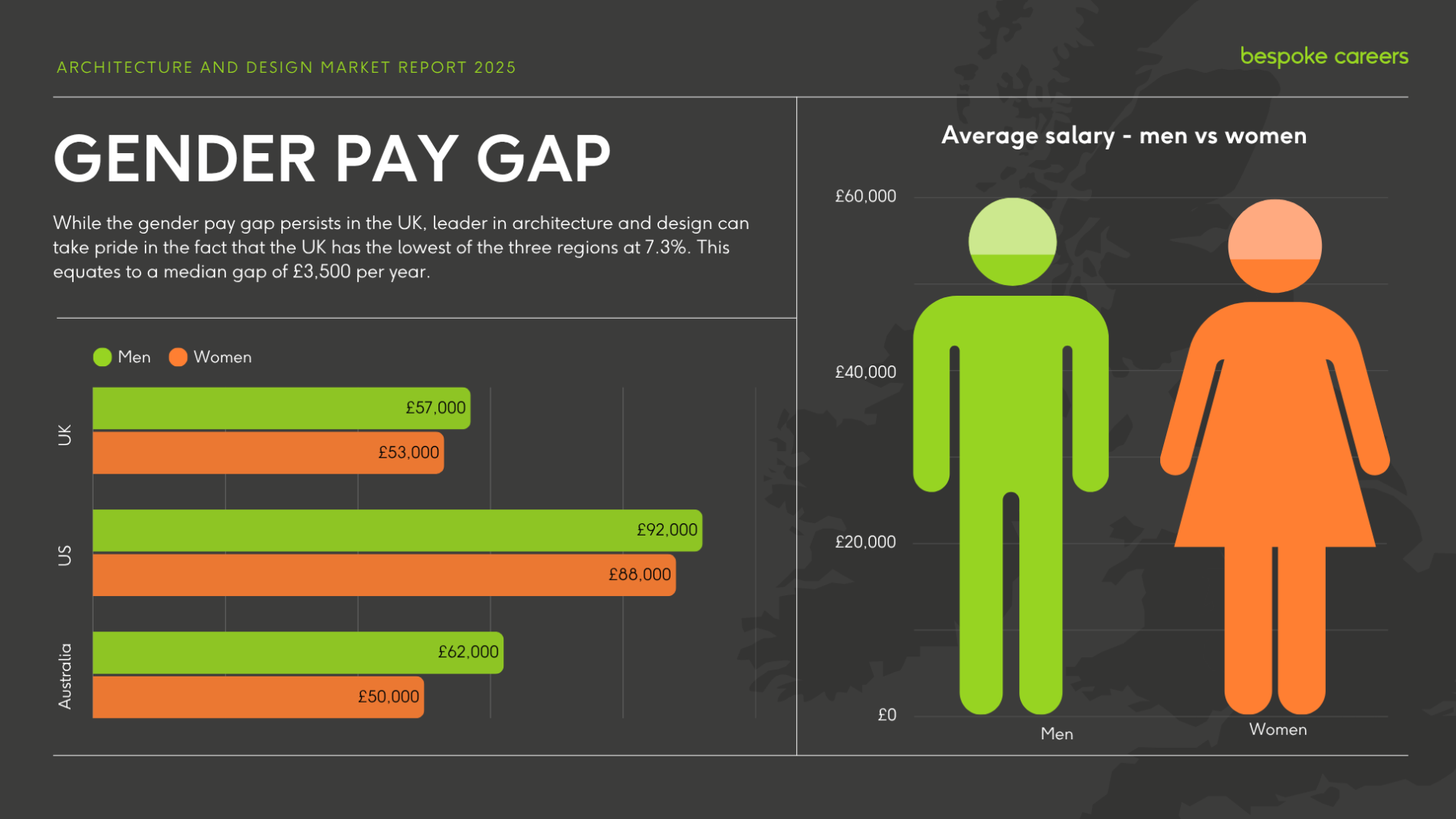

Gender pay gap in architecture and design across the UK, US, and Australia, 2025.

It’s still a huge problem. And it’s fragile. It doesn’t take much to lose ground. A recession, a pandemic, any kind of crisis, and the first people to go are often women, minorities, or those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

In the UK, I noticed a drop in diversity in student projects after fees went up. The range of ideas narrowed. That’s what happens when diversity decreases. The work itself changes.

The conversation about diversity is broader now, but the work isn’t done. It’s not just about getting women into the profession, it’s about keeping them, through childbirth, through the challenges of raising young children, through menopause.

The gender pay gap is a good indicator of progress. If women aren’t in senior roles, you don’t get the full range of voices and perspectives in decision-making. And it’s not just about gender. You need balance between introverts and extroverts, between different ways of thinking and speaking. We design cities for everyone, so we should look like everyone.

Angela’s experiences with gender discrimination

I’ve made a point of working in places where I’m heard. That’s important to me. But bias still shows up.

I remember being on site with a graduate and having all the questions directed to him, simply because he was a man. He was baffled. I had to explain, “It’s because I’m a woman.”

Australians, in my experience, also love a bit of sexual innuendo in the workplace. Sometimes I’ve had to say, “This makes me uncomfortable. This isn’t appropriate.” I feel empowered to do that now, and I wouldn’t work anywhere I couldn’t speak up.

Advice for young architects finding their voice

It’s not just about gender, it’s about all the “isms.” You might feel like the only person in the room who represents whatever it is you represent, whether that’s age, background, or something else.

Find rooms where people want to listen to you. That’s been a guiding principle for me.

Careers are part design, part luck, part timing. You can’t control it all, but you can hold on to who you are, what you believe in, and how you want to work. For me, that’s meant working in nice offices with nice people, doing architecture in a nice way.

Young architects today are much better at stating what they want from a job, and I think that’s great. Leaders should listen.

Has her career turned out as expected?

Not at all. I didn’t expect to be starting a business at this age. It feels a bit like going back to being a student. My head spinning with everything going on at once. But I’m proud I’ve done it.

You can’t gloss over the fact that it’s still an architecture career. There are always projects you don’t expect. One of my last at Grimshaw was a recycling centre in Edmonton. At first I thought, “That’s a lot of rubbish” – literally. But it turned out to be fascinating. The client was great, the team was great, and I learned a lot about processes and materials, including how bad plasterboard is for reuse.

Architecture will surprise you. Even small projects can be great projects. This career hasn’t unfolded the way I imagined, but I recognise myself in all of it. And that was the intention all along.

Looking to hire top talent

or advance your career? Let's talk.

or advance your career? Let's talk.

We connect exceptional firms with talented professionals.

Let’s discuss how we can help you achieve your goals. Get in touch with the team today.

Related Posts

Making architecture more accessible, more adaptable and more collaborative by rethinking how we build, who we serve and how we listen.

Job interviews via Skype and other video conferencing software were once an occasional occurrence, but they have now become the norm as the world works from home during the Coronavirus outbreak.

The Bespoke Careers 2025 Architecture and Design Market Report reveals architects and designers are prioritizing wellbeing over traditional work demands.