How a Fashion Designer Became a World Famous Architect – Kathryn Gustafson

Founder of Gustafson Porter + Bowman, Kathryn Gustafson reflects starting a studio in a second language, and learning the business side of practice through trial, mentors, and persistence.

Kathryn Gustafson has worked on some of the most high profile, complex public landscapes in the world, yet her best advice is simple:

Slow down.

From fashion in New York and Paris to landmark projects like the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain, she explains why landscape looks effortless only when it’s been thought through properly, why big projects demand patience, and why the work matters too much to rush.

Seeing the world differently from other people…

I have always seen the world I see. Now, is that different from other people? I have no idea.

Impact of the desert…

I think that my situation probably is special because I was raised in a desert where water was a resource that was very precious, guarded, conducted, and conveyed. That appreciation of a natural resource and the danger of it also is very much part of it because you have these channels of water that are just running and that were created by the Army Corps of Engineers. The place is called Yakima, Washington.

As a child you had this water just racing past you and everything around you was desert unless the water touched it, and then it became paradise. It has affected me very deeply and has made pretty much everything what you see in a landscape. You really have to try to understand what you are looking at. It is not self-evident that you are going to understand it immediately or without just taking time to pause. Some people can, maybe.

Yakima, Washington. Image: AirLiner

Discovering design…

I actually started in art and clay when I was thirteen and I just realized that it was the happiest place I had ever been outside of sports. That was also a very good place for me, but all of a sudden it fit. Something made sense. I never turned back. I went from thirteen to high school to art school. There was not anything else I wanted to do or I could do. I did have a period at one point where my dad, who was a doctor, said I should go into medicine. I did not even get through two days of chemistry before I said this is not going to work. I went back to the studio. I did not have any heart-rendering decisions to make. Design was natural. It was the one thing that always just fit. I am lucky.

Entering the fashion world…

FIT Portfolio, 1970 © Kathryn Gustafson

That started out quite early when I was fifteen or sixteen. I was a tall, red-headed, lithe person, so they had me modeling and I found it super boring and short-term. I started making things and my father was very supportive. He would buy me fabric. At one point he said that I could not have another piece of fabric until I finished the last one. I just started making things.

Then I went to the University of Washington. The only place to do that was to do art as sculpture and home economics. It is weird, but it was a long time ago. I applied and got into the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, which was just unheard of. I had a full ride and that was it. I was off and running and moving away from home.

Moving to New York and Paris…

I remember walking into an advisor when I was sixteen. I said I was going to go nuts if I stayed there and asked him to get me out. He asked how far and I said as far as you can get me. He sent me to New York to do a summer program. I remember riding a bus into New York City on one of those turn ramps. My thought was that you can do anything here. You can find everything. You can find people. You can find things. Everything is available in New York. That was just an explosion of possibilities. That bus ride into New York City was magic.

Leaving fashion for landscape…

Fashion taught me a design process. It is a very clear process that has a start, a medium, and an end. It has four seasons and all different types of experts, including the people who do the color, the tailors, the fabrics, and the marketing. Fashion is complex. It is a great way to learn how to design something, go through that complexity, and come out at the end with something that is truly beautiful. That is a lesson for the rest of your life.

Part of me knows that if I had just stayed another five years, the whole world was changing. We were changing from a world of designers that did huge collections to what we call boutique designers, like Issey Miyake and others that did smaller collections. I was gone by then. If I had stayed I probably would have liked it because the collections were smaller and more in control of an image and of a signature. But by then I had moved on and I am really glad I did. The part that I moved away from in fashion at that time was the big collections. There was an underlining dishonesty that was so fundamental about making money instead of making beauty at the level I was at. I just said I am out of here. I am not spending my life like this.

Choosing landscape architecture…

It was already a choice that had happened three years before. It was having a glass of wine with a friend who I asked what she wanted to do. She said landscape architecture. I felt like I was the Disney mouse that somebody took a bat and just hit me across the head. I just went, oh, that is what I am supposed to do. She told me I better go research it. I spent two years researching it, going to different people, reading, and trying to figure out what it meant. It was the best decision I ever made in my life.

Returning to school in France…

Re-learning was easy because you knew all the tools. You knew how to learn, how to discipline yourself, how to work with teams, and how to draw. What was not easy is that I did it all in French. That brings some difficulty. I had a tutor who was my professor in land law. He would spend hours with me explaining the terminology. I had very kind people around me help me with the language and the culture. When you are learning in France, you are in a Napoleonic code culture. In something like architecture and landscape, you better know what you are doing legally because you can get in a lot of trouble.

I knew how to draw, but I did not know the core things about landscape like soil, water, and plants. I know the fabric you are wearing and what seam was sewn there, but the tools of landscape are totally different. The day I decided to change, I was at the Parc Floral de Paris in Vincennes. There is a beautiful sculpted piece of land that was done in 1975. I looked at it and saw it was designed by a man named Jacques Sgard. It was an art piece. That is when I said if I can do this as an art form, then I am in. I did not want to do a nursery. It was so sculptural that I decided to make this an art form. Then I got him to teach me.

Balancing business and art…

You have to make a living and you are an architect. We have contracts, insurance, and all the pieces that make the piece. You have to do those things or you do not get to do what you want to do. You cannot just pretend and lollygag around. These are part of your tools. It is not a game at all. It is about making your vision possible. The tools are there to help you, not to pull you back. They are there to get you through. You have to design something that you can actually build, that people actually can use, and that they actually like.

Starting an office…

Nobody would hire me because I was older than other students coming out. It was my second career, so I was only six or seven years older, but I also had attitude. Nobody really wanted to hire me because I would just want to design and they had their office because they wanted to design. I ended up opening an office that was basically one person and doing some French government work. I studied the work of Ian McHarg, who is the father of landscape analysis out of Penn State. He taught how to understand where to put a freeway or housing by looking at the national environment and everything in your landscape.

Slowly things happened. Because I had done clay before fashion, one of the teachers at the school suggested we do clay. I knew how to do it. It was that moment when I knew that clay and land movement were a marriage. It was something I was really comfortable with and something where I could express myself and understand what the landscape could do.

Image: Charles Hopkinson

Navigating the invisible years…

You just start small. You take small jobs where you learn. I was very lucky. There were two men about ten years older than me that needed somebody to help them with their projects. They had an extra room in the Latin Quarter and they gave it to me. When they needed some extra drawing, I would help them and they would teach me how to write a contract or explain different parts of the field. They took me under their wing and spent two years teaching me the ins and outs. I often traded things I knew how to do for people to teach me. I traded photographing projects for one landscape architect in exchange for him teaching me how to draw. I have always traded things.

The power of publishing…

I had a really good friend named Peter Rice, and we worked at La Villette together. He was a real mentor for me. I asked how I could become somebody that people want to hire, and he said I had to publish. He told me I could not just publish one project, but that I had to publish five. I held back for three years because Peter was right there with me. When I had five good projects, he said I was ready. I came out in five different magazines in three months with five projects and it was just like boom. Somebody told me what to do. I owe him a lot.

On social media and communication…

I am not part of that world, so I really do not know what to think about it. Everybody communicates and thinks differently, and I think that is one of the beauties of design. It comes from a place. It has to be part of you. When you put your pen to paper, it is your pen to your paper and nobody else’s. Social media takes a lot of energy to do right, and I do not think I am very good at it. I do not want to be good at it. I would much rather go back to the quiet years.

I guess you need it because people need to hear and see things. There is a social moral obligation to teach, educate, or give back. That is probably why I am doing this, to try to help other people find their way. The whole world of landscape architecture is not understood in its complexity. There are many different venues and ways that are all good. It is about which way works with your sensibility, your clients, and where you live. I do mostly public work and you have to figure out what the public actually needs. What I hope does not happen is that there becomes just one way of doing it. That would be such a shame.

Securing new projects…

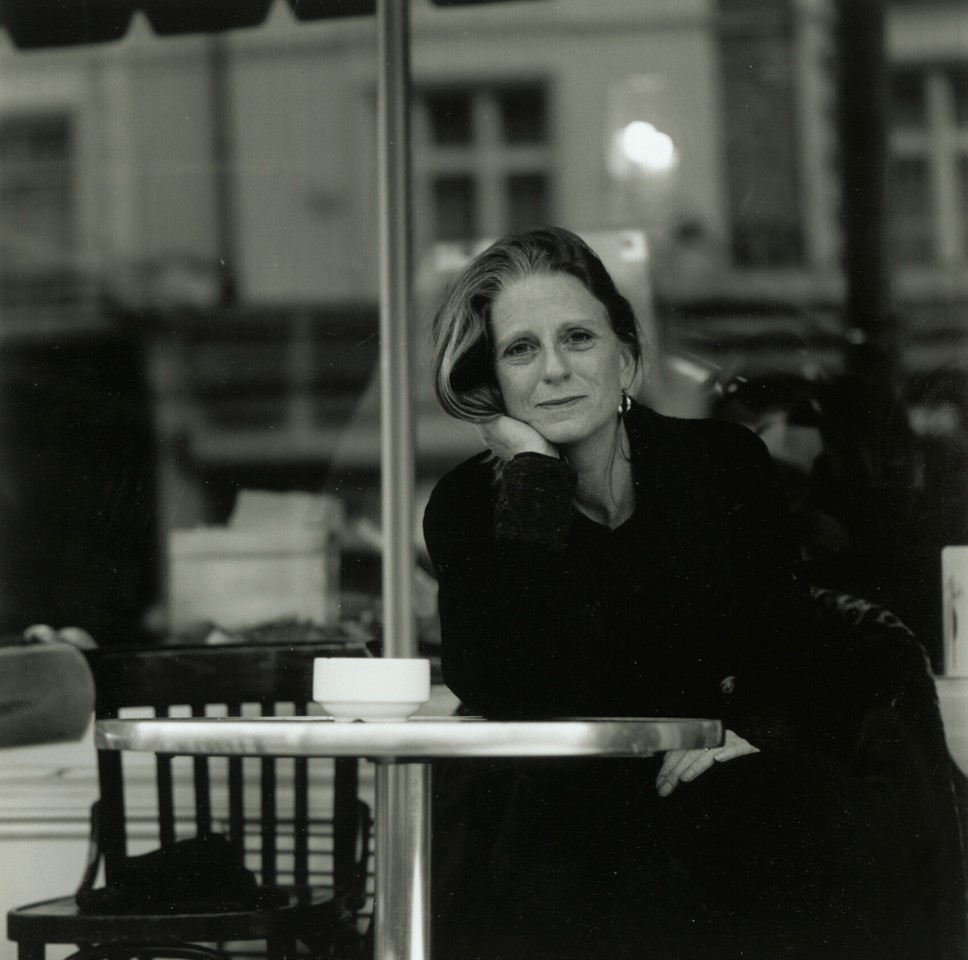

Grand Site Tour Eiffel, Gustafson Porter + Bowman + Sathy, Paris, © Lotoarchilab

It does not happen overnight, but slowly good work leads to good work. Getting good work out there means somebody might pick up a phone, but you still have to just do good work. Being stubborn and brave about good work is really important. I have crossed swords with certain architects because the work has to be good and it cannot be compromised. I often find that it is just not understood what it is going to do in five years.

Establishing international practices…

Opening two practices across different continents was related to my father. He was dying and I wanted to be there. People found out I was there and I started getting work. I needed help doing the work. I tried one practice that did not work out due to wrong ethics, but then I found a couple of people that fit great. They had lots of energy and a good education. I spent half my time there and half my time in Europe because I had my office in London. I moved my office to London because I needed to go back to the United States. Neil Porter and I worked on the Villette Park together and were very good friends. I asked him if he wanted to do landscape and he said sure. We packed up a U-Haul truck in Paris, drove it to London, and started an office.

The process of starting over…

I always find it fascinating. I would do it again tomorrow. I like that process of learning. I just wish I was thirty years younger because then you have more energy. It seemed at the time the right thing to do. I had work in Europe and I wanted to be with my family. I went and bought a house next door to my dad and I balanced that for twenty-five years.

The value of partners…

Having strong partners allowed me to be in that position. Partners are critical to a broader understanding of things. How you understand things will not be the same as how I understand things. Having those conversations helps you get to a place that makes sense for the piece you are doing. It has to fit where it is.

When you are in an art museum and you see a painting that makes you want to live with it for the rest of your life, that moment of connection is so rich. If you can do that with a landscape, people will take care of it. They start owning it and it becomes theirs. That connection is what I have always wanted to make. When they walk in for the first time and feel they want to be there, that is a landscape that will live. They have appropriated it and they will maintain and protect it.

Leading with Swedish discipline…

I am Swedish, so I am very straight and disciplined. I do not even have to try. Nothing floats except when I draw. I love that Swedish discipline and due diligence that I got from my dad. It is obvious that you have to do that to make it work. You have to pay attention to what is going on and think sideways to solve it. It has always been easy. There are days you draw and days you do not draw. Those days you do not draw are about logistics, finances, and all the things you have to do to make a business work.

Working with advisors…

Having really good advisors has been pretty magical for me. There have been key advisors that have popped in at the right time. You have to find the right ones who sit you down and tell you how to grow, how much money to spend, and what you should and should not be doing. These were specific advisors for the architecture field, not people teaching you how to market a grocery store. Having those people who are not in your field is huge. They are outsiders and their sole interest is you. I met one friend when I was twenty-three who stays with me as a personal friend. Any major move I do, I still go to him today.

Creating a workplace culture…

I want the environment to be structured, comfortable, and have lots of light. It should be quiet, accessible, and not imposing. I want people to have a lot of tools to allow them to explore. Those tools can be entire walls of stones or material things. We bring in people who teach software creatively. I just try to create what I would want and hope I have done it right.

Handling public opinion…

I ignore controversy pretty much because it is often coming from a place that has nothing to do with the work. There are different priorities with different people, whether they are ecological or financial. I do not know how much my work has actually been criticized versus it being about something else. You have to get things in context. You do not really know why things are happening behind the scenes, especially here in England.

Connecting with the public…

Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain

I see people walk up to me today and say how much they love the Diana Memorial. I do not think people walk up to me to tell me they hate it, so I only see the nice part. When I opened the Valencia Central Park a couple of years ago, people were so happy. This railroad yard had cut off neighborhoods, and all of a sudden they could walk out of their houses into the park with their kids. To see that happen is magic. I just opened a project in Osaka and the public opening was very positive. The kids were happy, the parents were happy, and the plants and trees were happy. It is a pretty happy field to be in. It is hard to open a landscape and have people hate it.

Architecture versus landscape…

I think architecture sometimes is not made for people, but for a person or a group. Public landscape works are made for the public. They are not even comparative. One is a closed-door piece that shows a facade within a city context. The other you walk right into. There are no closed doors. People have connections to landscapes that are very varied and cultural. Whether you are from the north, from Holland, or from Spain, it is extremely cultural. My biggest battle is trying to get that marriage between the place and the people. You are not designing for you, but for the place and the people you are in.

Navigating cultural contexts…

You are built by your experiences and your education, but as a designer, you have a natural curiosity to understand where you are. I remember the first time I landed in Beirut right after the war had finished. It was bombed everywhere, yet there was a culture there that was so rich. I loved trying to understand what happened. We are naturally curious because we want to discover, unfold, and create things. Where I came from gave me discipline, but curiosity is something you learn early on. It is your world and your discovery.

Embracing a slow pace…

Architecture and landscape architecture happen over years. The big projects are ten years minimum. Sometimes I squeak by at seven, but that is rare. You just have to breathe. The impact of what you do is so serious that you do not want to go fast. They are so complex that you do not want to go fast. Somebody who goes fast is either the most brilliant person in the world or they are going to miss ninety percent of it. I like the slow pace. I like it to calm down to see what we are doing and who we need to talk to.

Smaller projects are also lovely because they take a year and you learn about one specific thing. It does not bother me. You need to balance what you are learning and what you are giving. Someone might tell you they care about a wetland that you did not even know was there. Then you have to go study it and understand why it is there. It is like a good novel where the complexity just keeps reinforcing itself.

Skills for managing complexity…

The key skill is having good partners who say, “Wait a minute, did you look at that?” or “I think they are talking about this.” You have to sit down and ask what you missed. Everybody comes with a set of talents in their brain. I have had partners who tell me to slow down because one thing has to happen before another can happen.

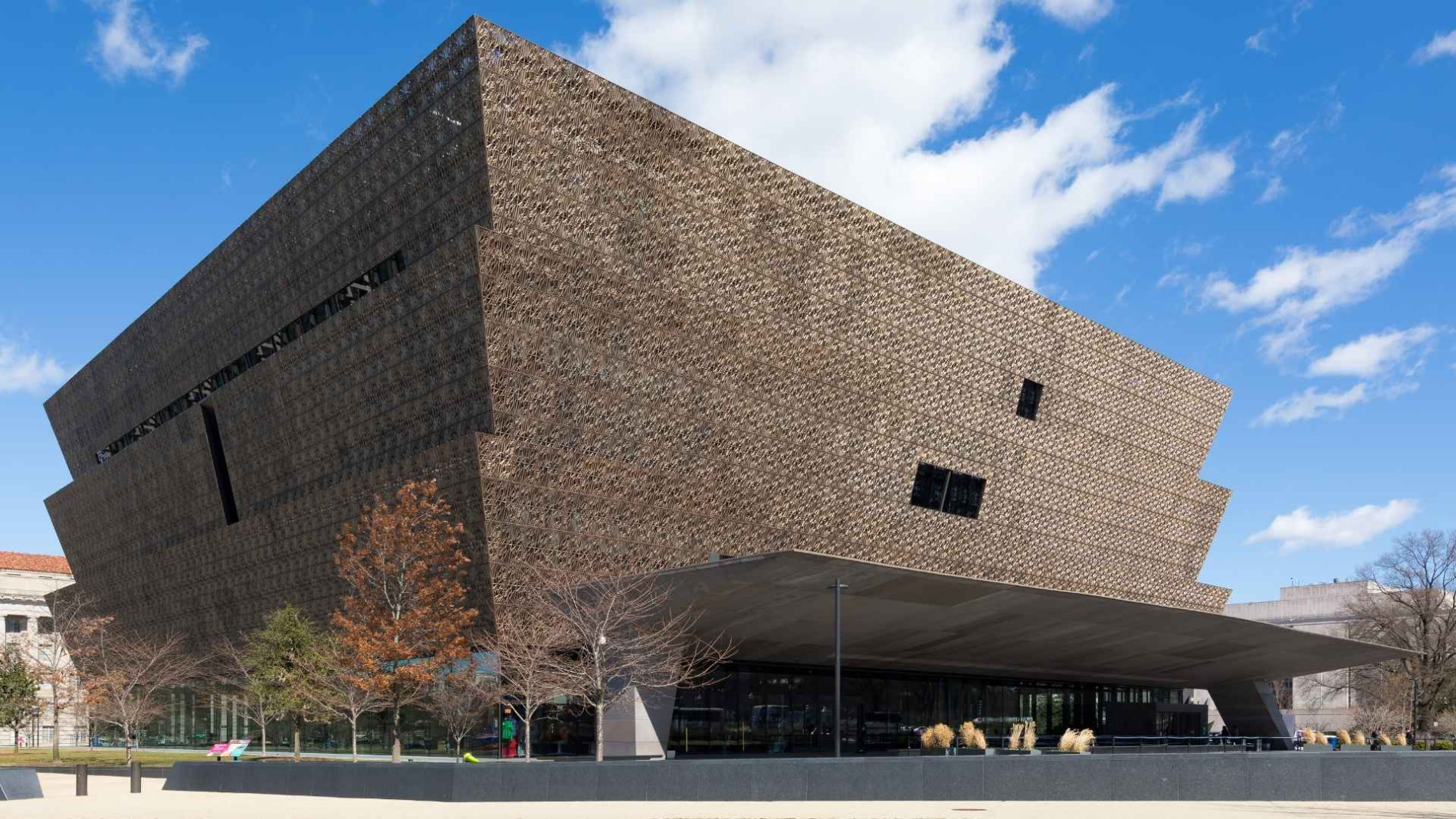

Working on the American Museum of African American History and Culture took seven years to build one city block. I learned a lot between the commissions and the architecture. David Adjaye was the architect and there were local and American architects involved. It is on the Mall in the middle of Washington DC. Everybody taught me something. It is about having those voices that can convince you that you actually need to look at something else.

Collaborating with architects…

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Every relationship with other designers is special. It is about whether you connect and trust each other. That trust is huge. It is also about knowing when you are over your head and saying you need help. Architects always think they can do everything. They probably can do everything, but not very well. They do some things fabulously well, but trying to get them to understand that landscape is a little more complicated than they think is sometimes a pain. It looks simple, and the whole art of doing it is that it looks simple, but it is not easy to get it right.

David Adjaye never pushed me on the landscape. He had so much to do that when I needed his advice, he was there. Landscape architecture is an amazing field, but trying to get projects like the one in Osaka built right, on time, and on budget is hard. it takes a lot of work and community involvement.

The aging of landscape…

There are different types of landscape. Some of the earlier sculptural works are exactly the same because they are land movement, lawn, and water features. Nothing is growing except grasses, so those pieces do not really change. Plazas do not change much either. Every plaza I built with François Mitterrand in 1990 is going to be renovated now, which I am delighted about because after thirty years it needs it. They are taking all the original plans to do it.

Certain landscapes age like a building. You need to redo the windows or the facade. With a beautiful historical building, you are not going to rip the facade off. It is called maintenance. The landscapes with more vegetation require maintenance plans for ten years. We predict where it is going to go and we write the manuals. The client can come back if it is not working and we relook at it. You are never going to get it right one hundred percent, but if you make eighty, you are doing great. It grows and it is alive.

Predicting the use of space…

The big problem with accessible landscapes is how they are treated or mistreated. You have to see what you have not predicted in the use. Maybe you need a pathway that you did not include, or a path is not wide enough. Maybe there is an invasive species you did not know about that has to be ripped out. You have to adjust with your client.

Most of my landscapes are well loved and in good repair. I wish the Jardins de l’Imaginaire in Terrasson was better maintained and revived to the original concept. It has been left to be overgrown and the complexity of the vegetation has been lost. It was one of my very first projects and it is extraordinary. Those were key pieces that were designed as experiential public parks and they need more care.

Thoughts on legacy…

I am not sure my legacy really matters. It matters more that people understand the legacy of landscape. It is a very complex, growing field involving people, plants, and paving. I think we can do a whole lot more as we learn more about native balance. There are many really good people doing great work. It is a vast field. For me, it is one of the most complex fields because sociology and many other areas all come together into this thing that looks simple.

The next generation of designers…

I think the next generation is smarter than I am. They know the future more than I do because they are in this changing climate environment and they understand the urgency of it. It is a planetary urgency that is beyond making a park next door. They have to figure out how to impact this global problem when they have so little power and the people who have the power are mostly not doing enough.

We have to get to the broader public to say that you are not going to have a planet. We have to wake up. My field is wonderfully placed to be part of that conversation. I am hoping young people just put on heavy boots and walk in. It is not just protecting the environment, it is creating the environments for people to live in with intelligence. It takes a lot of people together to do it. You cannot just sit on a bandstand. You have to get governments together and elect the right people.

Reflections on a natural path…

My career has been pretty natural. I do not know how to do anything else. I can design and I can sew, but I am not really good at anything else. I loved it and it loved me. I am very thankful that I have been able to work with so many great people and great sites. I have every intention of continuing the premises I started out with. If I can make this an art form, I am interested. I am still interested that it is an art form and making that piece work on many different levels is very important to me. Whether it is a drawing, a model, or something built, those are all part of it. I have had a blast. I am so lucky that I found it.

Looking to hire top talent

or advance your career? Let's talk.

or advance your career? Let's talk.

We connect exceptional firms with talented professionals.

Let’s discuss how we can help you achieve your goals. Get in touch with the team today.

Related Posts

The Bartlett Ball 2025

Celebrate architectural creativity and innovation at The Bartlett Ball 2025, showcasing student work and fostering networking.

RIBA President Chris Williamson reflects on discovering the profession, building a practice, and how to regain architecture’s influence.

A new report by Bespoke Careers reveals the UK architecture and design industry is showing signs of recovery, but still lags behind international peers on several key metrics.