An Honest Conversation About Architecture School – Lucy Carmichael

Lucy Carmichael explains why the traditional, linear path into the industry is failing most students, and what the alternative looks like.

Lucy Carmichael is and Architect, former Director of Practice at the RIBA and current Board Member for the University of the Built Environment.

From her upbringing with architect parents, to navigating the “heyday” of design policy at CABE, Lucy has spent her life ‘falling in and out of love with architecture.’ The thing that keeps her coming back is the huge potential for positive impact on society.

We explore the “radical realism” of the London School of Architecture, the looming impact of AI on graduate roles, and why the most impactful architectural careers are often the ones that look the least traditional.

On the earliest seeds of an architectural career…

Architecture was never a vocation for me. I grew up in a house of architects. Both of my parents are architects. Perhaps that is why my instinct was to go in the opposite direction. I grew up in a house designed by my parents and lived and breathed the experience of the profession from the family side. I did a year of modern languages, but the creative itch still needed to be scratched. Someone suggested to me that maybe I should consider switching to architecture and I did. I think it is still true to say I always felt like a bit of a fraud compared to some of my contemporaries who were so clearly driven by the profession. I did not count myself among that number.

Lucy and her sister in costumes designed by their architect parents.

On growing up with architects for parents…

The Carmichael Residence in Liverpool, Merseyside

It was overall a really positive experience. I definitely internalised the benefits of good design. The house they designed was an early example of energy-efficient architecture. It was basically a passive house design, built in the 1980s, so really ahead of its time. I saw both ends of the profession. When I was very young, my mum ran a kitchen table practice, as is common with many working women. My dad ran a successful architectural practice in Liverpool which is still going to this day and still bears his name.

They both taught, so I saw the full spectrum of professional life, with some ups and downs of crises and projects gone wrong. I largely kept my distance from it. It is quite common for young people as they are growing up to seek to differentiate themselves. I pulled in a different direction.

Lucy Carmichael Aged 2

On her experience of architectural education…

My experience in architectural education was very much of its time. I did an undergraduate degree at Cambridge, which at that point was a highly theoretical course. That worked quite well for me in terms of transitioning from a language degree and enabled me to carry on my theoretical interests. I was aware that any of the nitty-gritty aspects of the practice of architecture were kept to the lecture theater. Structures, construction, and environmental design were taught in an equally theoretical way and did not really get applied in practice. That was quite comfortable for someone like me who was interested in architectural ideas and the creative process of design.

I have had a very non-linear career route, including my education route. There was a full four years between my Part One and my Part Two. I have never been on that very linear path through the profession, the seven-year rule. I have been falling in and out of love with architecture and being distracted by other things as I have gone along the way. Overall that has been a really positive thing because it means I have always kept a bit of perspective on architecture and on the profession more broadly. For as much as I have lacked a vocation, I came for the creativity but I have stayed around for the impact that I have seen architecture can have. I have made a career out of supporting processes that make sure that impact can be as positive as possible.

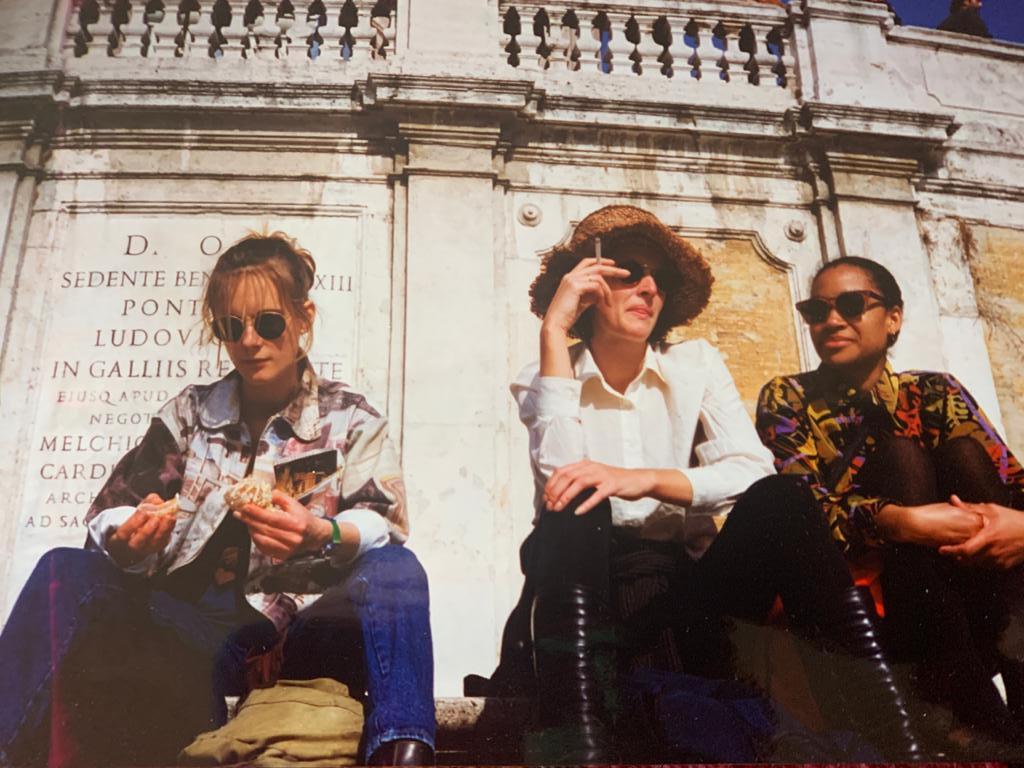

Lucy during her first year of Studies. 1993

On navigating her early career in practice…

I was really lucky. My first experience was not great. I graduated in 1995 at a time when there was a lot of economic instability and people lost jobs. We were all encouraged to take the first job that came up. I spent half my time doing stone surveys high up on scaffolding on my own. No one was there to see if I fell. The other half of the time I was getting up at five in the morning to travel down to Croydon to a multiplex cinema.

I stuck it out for six months, took a bit of a break for two years, and then went back to work for Tim Reynolds for two years. That was an absolutely brilliant experience. It has made me reflect on how much luck is involved in terms of the practices you get to work for and the culture of those practices. Tim Reynolds was still quite small then, working on fantastic Arts Council funded projects. There was a nurturing and trusting culture, even for Part One students. My first week I was sent up to Hull for a few days to do a full analysis of ten possible sites for a new center for the arts. I was entrusted to do the feasibility study.

Those kinds of experiences are why I fell back in love with the idea of working in architecture. I was very lucky to be mentored by Chris Watson. Both William and Mary Watson were there at the time. It caused me to reflect on how important practice culture and those formative experiences are for Part One and Part Two students in making decisions about whether they take their career further.

On the transition from practice to CABE…

The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) was an executive non-departmental public body of the UK government, established in 1999. It’s job was to influence and inspire the people making decisions about the built environment.

The thing that has characterised my career has been responding to opportunity and being in the right place at the right time. I was actually made redundant from the small architectural practice I was working for. Within an hour of being told we had been made redundant, a few of us were on jobs websites and this opportunity had come up at CABE. It was a maternity cover. I thought there was no harm in leaving the profession for nine months. It sounded really interesting and the pay was good. I had about two days to pull an application together, got the job, and ended up staying on for seven years. I fell out of the profession rather than left it intentionally, but there were good reasons why I chose to stay at CABE rather than moving back into practice.

On the influence and ethos of CABE…

I was really lucky to be there at the heyday of CABE. I joined two years after it was founded and it really did feel like a movement. It felt like we were part of something really important. It came at a time when the government was willing to sponsor an architecture body of that nature. We had a fantastic, dynamic leader in John Rouse. It relied on the voluntary expertise of leaders in the profession and the wider construction industry. That is something I have kept with me, organizations punching above their weight by using the pool of expertise across the profession.

It felt very powerful. Not just design review, but also the CABE enabling program. It is an interesting indication of the success of CABE that so many of my contemporaries are now embedded in incredibly senior roles, such as chief planner or chief architect, or leading client organizations. I did a piece of research about the impact of CABE regarding the London 2012 Olympics, but it would be interesting to see where all those people are now and the impact of the ethos they have taken out into the world.

The core CABE principles and guidance continue to hold true today. Working in design review has gone on to have a life after CABE, but that early model was independent and focused on strategic development projects. Over time we saw the impact of the feedback we gave. I can walk around London and see projects where I know CABE had a hand in nudging it in the right direction. What is more interesting are the many projects that did not go ahead because they received a fundamental rethink letter. Those potentially would not have had a positive impact on our built environment. It was a positive time with a fantastic organizational culture. It knew exactly what it was doing and had a clearly defined process to get the best out of experts and deliver the best advice.

CABE Design Review

On communication and design review…

There are two sides to this, the presenting teams and the design review panelists. Regarding the panels, one of the key principles we worked within was that panel members should never cross the line into design. Keep your pencil in your pocket. It was an analytical process about identifying issues that needed to be addressed. There was an art in articulating what they were. I was always incredibly impressed by how panelists really got to the heart of why a project was not quite working, but they always articulated that as a question or provocation rather than a solution.

When it came to presenting, some architects were just fantastic storytellers. The most memorable presentation was from a very young David West. He was presenting his vision for the Bradford Bowl and he was an absolutely brilliant storyteller. There is something about understanding how your work is going to connect with its audience. Architects can be very involved in their own thought process and do not make that next step to articulating that as a story which is going to connect with the audience. They do not step back and look globally at why it matters to whoever they are talking to, whether it is a design review panel, a planning authority, a client, or a funder.

There is a danger that architects do not get beyond what matters to them. Most architects are purpose driven, but I am talking about the communication rather than what is driving them. In my generation, that possibly comes from architecture school where the model was to defend your ideas. From what I have seen at the LSA, there is a much greater focus on communication and teamwork. For example, they do a project in the first year called a Design Think Tank where students work and present as a team, have a real client, and are mentored by architectural practices. Storytelling is a huge part of that.

The risk is that those skills can get lost in the early career stages. Practices should be proactively looking for opportunities to put young architects in front of clients and give them presentation opportunities, even if it is just internal design reviews. Confidence can be lost quickly, but communication is a huge part of what architects need to do at every stage of making a project happen.

On moving to the RIBA…

Lucy was Director of Practice at the RIBA from 2015-2021.

I had a bit of a break and got an opportunity to do a research project. At CABE, I was given the opportunity to set up and manage the London 2012 design review process, which was the very first paid design review process. At the end of it, there was an aspiration to write about the learning legacy. I got the opportunity to write that research project, which worked well with where I was in my personal life with young children. I did that for a few months, took a short break, and went to live in India for a short while.

Following the pattern of my career, I came back on a Sunday night and looked on Guardian Jobs. There was a role at the RIBA and the deadline was the following day. I was applying for a PhD at the same time, which was another sliding doors moment where I could have gone back into academia. I got the role at the RIBA, which had strong similarities with my work at CABE in terms of working with leading minds, but with a focus this time on the practice of architecture rather than architectural design.

On the differences between CABE and the RIBA…

I think it is an unfair comparison because their operational models are completely different. One was a fully publicly funded body at a time when there was reasonably generous government funding. It could focus entirely on its purpose. There was a much greater clarity around what it was set up to do and who its stakeholders were. A membership body that is also a charity is a much more complex beast with a range of different audiences and drivers. In addition to being purpose-led, there is still a concern about the bottom line and growth. Those are different pressures on an organization.

On the priorities during her time at the RIBA…

I was at the RIBA for almost eight years, five of which were as Director of Practice. It was an interesting time with serious challenges. We had to respond to Brexit. The awful Grenfell Tower tragedy was a huge priority for the last four or so years I was there. There was also the COVID response. Ongoing themes included procurement, which I was very involved in. Procurement exercised members more than any other issue, particularly those from small practices, because of the sense of extreme unfairness in the system.

There has been some significant reform, but only a week ago someone was telling me about a project where it was still 70% cost and 30% quality. If you want to work in the public sector or the cultural sector, that is the only way you are going to win work. It still feels for a lot of practices that the odds are unfairly stacked. It is an incredibly time-consuming process. We also did huge amounts of work around sustainability, fire safety, and competence, which has been really significant and influential in the review process. It always felt like a very worthwhile role because we were working with members to tackle key issues for the profession and the public.

On architectural accountability and the insurance crisis…

A lot of careful thought went into the policy line on where the line should be drawn around architectural accountability. What has happened in relation to health and safety, the CDM regulations, and the principal designer role is helpful. A principle had been established that the lead designer should take on those duties. The outstanding issues are around fees and liability.

My inbox was never so full as when the insurance crisis hit and some practices actually closed. It was a devastating time with huge premium hikes post-Grenfell. We did work with Roger Flaxman, who produced a report on the professional indemnity insurance industry and the need to fundamentally restructure construction so that the right level of liability is sitting with clients and their design teams. That comes from the government level down. There is still a huge amount of pushing liability down the chain. The conversation around accountability, insurance, and contractual liability all ties together.

On the the RIBA’s communication with its members…

I do not think there is a general understanding of what the RIBA does. Having been on the outside for five years, I do not think it is entirely the RIBA’s fault. They have done a good job overhauling their comms to be much more profession-facing in the last ten years with the new website, brand, and newsletters. The issue is that architects are very heads down. I do not know whether they are looking up and paying attention to other institutions or if they are just so focused on the job that they are not aware of what is going on in the sector. Architecture remains an incredibly demanding and time-consuming profession. Unless you are actively looking to be involved or have time to read the newsletter on the way home, you are probably not going to be aware.

I was amazed to discover how much the RIBA had done that the practice I was working for was not aware of. Much of what we did in the Practice Department was producing resources to help architects make their business operations more efficient, such as templates and guidance. They just were not aware of these amazing resources that were there to help them. It would be interesting to see if there is a better platform for communication.

On member engagement and collective expertise…

The only way I could have done my job as Director of Practice was drawing on a pool of about 150 members who were directly engaged through advisory committees, task groups, and expert groups. They gave up their time and expertise for work like updating the Plan of Work, sustainability, and fire safety. None of that work would have been possible without them. Often it was a member taking charge, such as Dale Sinclair with the Plan of Work.

The gear shift after COVID toward less face-to-face engagement has changed the dynamic. There was something about sitting in a committee room and having that focused discussion a few times a year. When I looked after the Expert Advisory Group, one of the major things I tried to do was move away from talking shops and toward a task-and-finish approach. The role of the institute is not to waste people’s time and to ensure their efforts are directed toward concrete outputs. The role of the RIBA executive is to draw out the best from its membership and play it back to the wider membership.

On her involvement with the London School of Architecture…

Lucy became Chair of the Board of the LSA in 2024, overseeing its merger with the University of the Built Environment.

Neal Shasore had been in my team at the RIBA in the Practice Department. We kept in touch and he understood that practice department ethos. When he became Chief Executive of the LSA, he invited people he knew to mentor his team. I had been mentoring one of his team members for a couple of years. When the board looked to refresh their membership, they invited me to join. I sat on the board for a couple of years before finding myself in the position of Chair by accident. Our Chair had been headhunted to lead a bank in Switzerland. I was going to keep the seat warm, but circumstances took their course and I ended up staying for six months through the merger.

Ideally, a Chair’s engagement with a small charity would be bi-weekly or monthly. It just so happened that when I took on the role, there were matters requiring more active involvement, largely overseeing a merger with a university, which is not typical business.

On the ethos of the LSA…

Radical realism is clearly core to the ethos of the school, but not at the expense of creativity or challenging theoretical thinking. The school does a brilliant job of taking real-world challenges as a starting point and pushing those to their theoretical and creative limits. Because of the structure of the course, it attracts a certain type of student. LSA students tend to be quite entrepreneurial and self-possessed. They seem to really understand their creative and thought processes and leave with a clear framework for thinking about architecture and its purpose within society.

The fourth year of the course involves three days in practice, keeping a foot in each world. That dialogue between practice and studio work is really interesting. It is just as interesting for the practices hosting and mentoring students because they almost get the benefits of part-time teaching. It keeps them alive to architectural theory and thinking about why they do what they do. There is a genuine dialogue between studio-based research and what is happening in practice.

On accessibility and the future of the school…

The LSA model definitely gives an opportunity to students to take charge. It does not go as far as everyone would like because fees are still set at the full rate. However, for that first year, you are on a salary which makes a reasonable difference. Importantly, many LSA students stay with that employer, which provides continuity in a graduate job market that is pretty short at the moment. They maintain the currency of practical experience. It would be a longer-term aspiration for fees to be more competitive or for there to be a higher number of bursaries.

At a time when the government is closing the door on Level Seven apprenticeships, the LSA stands as a beacon of forward-looking education. Removing the apprenticeship scheme is a huge wasted opportunity. My hope is that lobbying will reverse that decision. If the door really is closed, I hope practices supporting apprenticeships will redirect their focus to hosting LSA students. It leaves them in a much better position regarding long-term career prospects than a traditional Part Two course.

On the merger with the University of the Built Environment…

The merger has put the school on a secure footing financially. Global factors and job cuts are affecting even the most highly regarded institutions and small educational charities. This has secured its future. There is also great alignment because the University of the Built Environment largely offers apprenticeships. Their whole model is around accessible, employer-based routes, so there is real synchronicity. They also have a research program focused on the sustainable built environment. The LSA can now focus on teaching a fantastic Part Two rather than just keeping the lights on. It has security without compromising its ethos. The recent appointment of Lee Ivett as the new Head of School is a clear signal that the radical ethos is going to be taken forward.

On the practice network…

The LSA would not exist without the practice network. They are fundamental to the model. Students cannot join the course without practice placements. Above and beyond that, many of the teaching staff are practitioners who run the Design Think Tanks. It feels like a movement where people really buy in. The school was founded by practitioners like Will Hunter ten years ago. They have given a huge amount to the school because they understand the need for an alternative education model and because they get huge amounts out of it as well. It has an amazing raw energy and is a vital place to teach. The practice network is absolutely fundamental.

On the impact of AI on architectural careers…

I am concerned about what technological change means for career development, from undergraduates through to early career and beyond. There is a real risk that more of the early career stage work can be done by AI. There will be a skills gap. As an industry, we need to be thinking about what that career path looks like so it is not just left as a void. There has already been a drop-off in Part One and Part Two recruitment in the last couple of years, which is concerning.

It is a commercial imperative for practices to think about what the new career path looks like for a student through to senior levels as the role adapts, rather than just not recruiting at that level and hoping someone else trains them. We could hit a huge cliff edge in ten years where everyone has left the profession because there were no jobs for them. This is likely to affect many service professions.

On professional responsibility and the skills gap…

That collective professional responsibility for the future of the profession needs to be part of decision-making about recruitment. We cannot leave it for someone else to worry about because the skills will dry up and talented people will move to other industries. There needs to be rapid and ongoing thinking about what this looks like.

I hear senior people in practice talking about the skills gap between university and practice. I think university is a good place to have those big theoretical thoughts. I would not want to just be teaching people how to use Revit in university because you would have a generation of designers that could not think in a certain way. However, the market is fearful about taking the responsibility for upskilling.

On the value of critical thinking…

It makes sense to have a close relationship between employers and education providers, provided it is not employer-driven and there is proper academic space for theoretical exploration and critical thinking. You want students to be really employable, and employability should be a result of their critical thinking skills. In this changing world, critical thinking is the value architects bring regardless of the sector. My architectural training gave me the ability to think critically about any problem and approach it creatively and collaboratively. Those skills have never been more important.

On her legacy and passion for social value…

I never really saw myself as an architect. I flirted along the way with other careers in film or academia. But I am drawn back to the architecture profession because you cannot get away from the potential for a huge positive impact. It has never been more clear that architecture practiced well and design delivered well could be fundamental in creating more sustainable cities and communities and making places safer.

I have seen how the work I have been involved in around the edges of the profession can make a difference. I am hugely passionate about the social value of architecture and accessibility into the profession in all its forms. I worked on diversity and inclusion, and was slightly disappointed after writing guidance about closing the gender pay gap in 2019 that it has not fully cut through yet. There is still much work to be done.

On advice for the next generation…

Lucy worked at De Matos Ryan as a Part II in 2001. She returned 20 years later as an Associate Director.

Our education system sets a particular model that suits a very small minority of people and then leaves everyone else feeling like they are failing because they are not fitting a perfect linear route. Your career path will be your career path and it will be different from the people you studied with. You do things at a time and in a way that suits you.

It is important to say yes as much as you can. If an opportunity presents itself and feels invigorating, take it. Explore opportunities that might be adjacent to careers in architecture and value the skills you have gained that are not just pure technical or design skills. Those critical thinking skills are broadly applicable and never more valuable. Just enjoy your career for what it is and do not benchmark yourself against standards that actually apply to very few people. Most people have had a slightly squiggly route.

Looking to hire top talent

or advance your career? Let's talk.

or advance your career? Let's talk.

We connect exceptional firms with talented professionals.

Let’s discuss how we can help you achieve your goals. Get in touch with the team today.

Related Posts

All designers want to make the world a better place. It’s in their DNA. But what happens when that ambition clashes with reality? How does that clash shape the jobs that we take, the people that we hire, and the careers that we build in 2025 and beyond?

Looking for insights into architecture salaries and design salaries in 2024? Our CEO and founder, Lindsay Urquhart, shares her thoughts on the global architecture and design market for 2024, and what to expect as the year unfolds.

Jimmy Bent explores how artificial intelligence is reshaping recruitment, and why authenticity and human judgement matter more than ever