Simon Allford: “The First 5 Years are the Toughest!” How to Survive Architecture

A wide ranging conversation with the AHMM co founder on growing up around architecture, starting a practice early, surviving the first five years, building a collaborative studio, and arguing consistently for architecture as a cultural project rather than a professional service.

Simon Allford is never short of a view, and this conversation covers the parts of architecture people usually avoid.

AHMM was founded in 1989 at possibly the worst moment in modern British architecture. Gold cards maxed out to cover office debt, competitions won but never built, consultancy work drying up. Those five years of survival shaped everything that followed. The rule from their student days still holds: the best idea wins, not yours or mine. If everyone’s comfortable with a design, it’s probably not good enough.

His infamous “first we storm the building, then we take back the asylum” quote came from genuine frustration with an RIBA he felt had lost its purpose. Architecture, not architects. The internal politics proved harder than expected: some figures were “sinisterly unpleasant,” but the House of Architecture concept survived. The collection is returning from storage, Portland Place is opening up, and he’s still chairing fundraising for the Museum of Architecture.

AHMM now has seven new executive directors and a global team of 400+. Growth was never the goal, they used to joke about never exceeding thirty people, but scale found them anyway.

If you want an honest take on what architecture is really like from the inside, and how to survive those (sometimes) brutal early years – this is a great place to start.

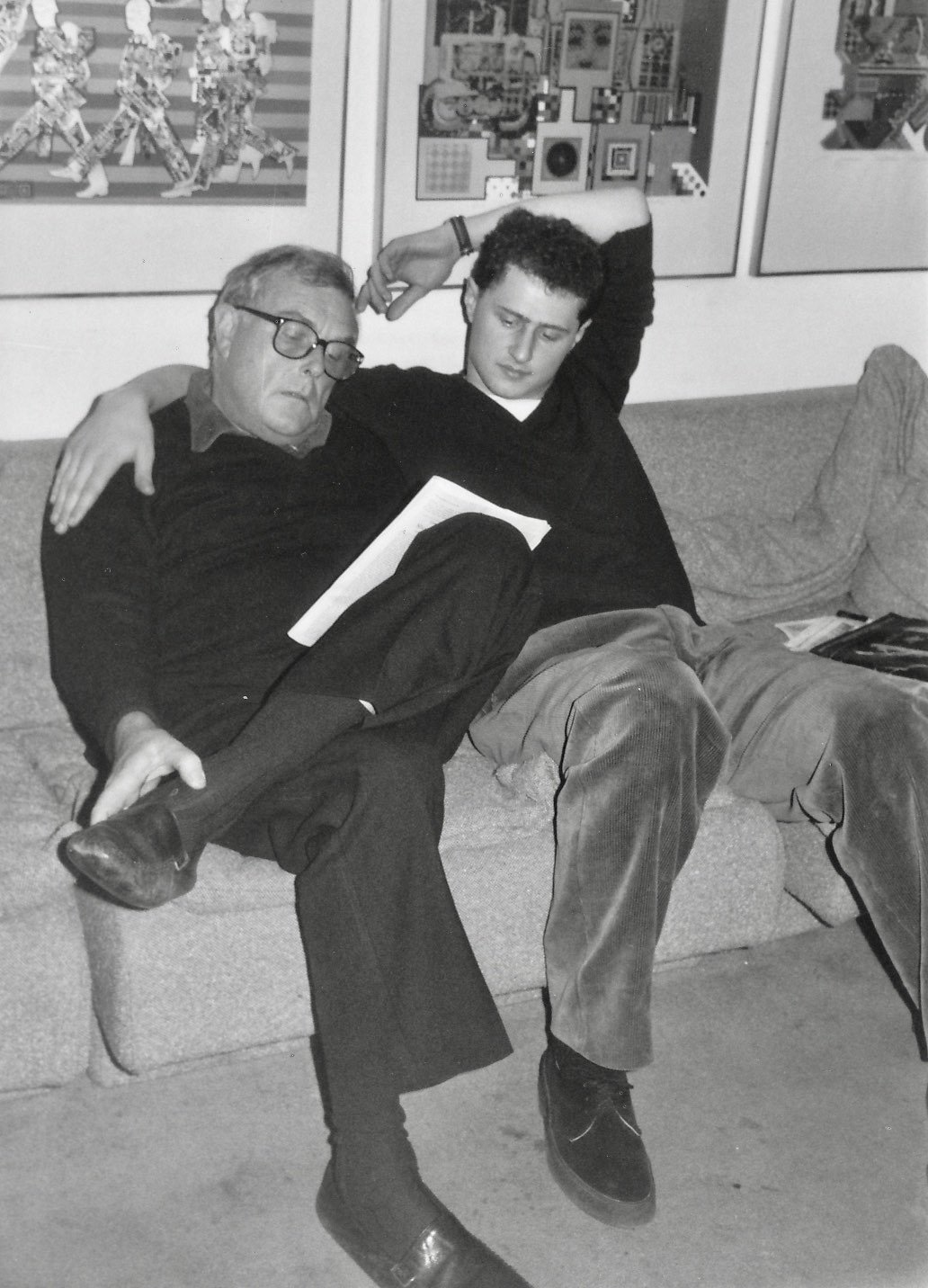

Growing up with an architect as a father and discovering architecture ‘on my own terms’…

Simon with his father, David Allford

I would say it really came together in my teenage years. I grew up with a father from the north, and a mother was from Redcastle. I grew up in London, but was always told ‘you’re a northern lad’. Looking back, I spent a lot of time being dragged around buildings and sites at weekends. He built a house in the country that we called ‘The Cottage’ – it was actually a modern brutalist box. I was surrounded by architects but I was not particularly interested. I wanted to be a footballer. Sheffield Wednesday, we lost 1-0 to Millwall at the weekend but that’s the way of the world.

When I was about sixteen or seventeen I was doing A levels in English, history and maths. I liked writing, I liked reasoning, I liked constructing ideas, but I did not want to be told which books to read and work my way through them. I always drew. I thought I might become an architect. My father said, in a nice way, “are you sure you want to do that? You will certainly never work for me.” And I said, ‘no, I want to to do it. I’ll see how it goes.’

I went to Sheffield and discovered architecture again on my own terms, away from him and away from practice. In my first year there was a series of lectures about the post war rebuilding of Britain. Suddenly I realised these were all people I knew. The Smithsons, Archigram, Cedric Price, Frank Newby were all his very close friends. Frank Newby used to go to Sheffield Wednesday with us. That was a revelation. I was far more steeped in architecture than I had realised, and that turned out to be a good thing. I have other friends who were steered into it, whereas I sort of discovered it.

I still make those connections now. I met someone last week who worked with my father forty years ago. When I was president of the RIBA, I met a Sri Lankan who my father had employed. He was nervous and dad had talked to him about cricket so now I enjoy the connection.

When we set up in practice, people would ask me if I was related to him. I used to joke ‘only distantly,’ because I didn’t want to be my father’s son. I didn’t want to play on that card. But now I am quite happy to acknowledge it. I am currently working on the reinvention of an iconic department store, Cole Brothers, which he designed, which is a bit of fun.

My father lived life quite large. I used to have breakfast with him at seven in the morning at the Meat Porters Pub. In a way life looked quite good actually. It all looked quite glamorous. I think it’s quite important actually to make life enjoyable. Architecture is tough enough. You have to have some fun along the way.

Meeting the AHMM partners at university…

AHMM Founders Peter Morris, Jonathan Hall, Paul Monaghan and Simon Allford

I went to Sheffield with Paul Monaghan. We were mates. We then came to London and shared a house. He actually worked for my father at YRM – a very large practice, whereas I worked for Nicholas Grimshaw, a tiny office. Jonathan and Peter were in Bristol, living together, and then they came to London as well. It was a small, interconnected world, which I think is always the case.

We were the outsiders at Sheffield. We were the only people who had come from somewhere else and moved there, so we naturally gravitated together. We were probably a bit more adventurous because we had bothered to leave.

In the fifth year the project was a supermarket. It was probably quite a good project but we thought it was terrible, so we said we didn’t want to do it and invented our own project, the Fifth Man, about four people collaborating. It was a time of great change in the city. Function wasn’t the driving force. It was about making a place. We took a site at Little Britain and worked on a masterplan where we each had our own building wrapped around a public space.

We worked individually and collectively, never just collectively. You owned your project but adjusted it in response to the others, like neighbouring historical buildings. That project brought us together. Our tutor Jon Corpe suggested we go out and get a job as four. It was 1986. If you had a pencil you could get work. We ended up working for Bill Jack at BDP as a sort of tool within the office for special projects. We had a brilliant three years.

Learning by working and taking the leap…

In the evenings we were doing competitions. I was 27 when we qualified. We said either we stay and build buildings or we go before we’re earning proper money and open a practice. We decided one night in the pub to do it and resigned the next day, with notice. It was naive optimism.

We’d done very well in competitions. I’d won one for West Pier, Brighton. We’d had firsts and seconds elsewhere. It was 1989, the worst possible time to open a practice. But if you open in a bad time, you learn quickly. It gives you early agency and a level of security from mentorship.

The reality of starting a practice…

We had a soft landing because BDP commissioned us from our office. For 18 months it was okay. We advertised for loft extensions, did competitions, earned consultancy fees. Then from 1991 it got very tricky. Consultancy dried up. Competitions didn’t generate work. We were teaching, doing other things. Whatever we earned went into the practice.

Our accountant told us to get gold cards while we were still on salaries at BDP. At one point we were drawing cash on credit cards and paying it into the bank to deal with our debt. Jonathan Hall was a big gambler – we said let’s put some money on the horses. He said that was too much pressure. It was hand to mouth. You had to believe you’d survive. That’s why I always say to a young practice, if you can get through the first five years, you’re likely to survive. It’s about whether you have the energy and will to graft.

How we worked together as partners…

The rule was that anything you earned went into the business. That stopped people having sideline jobs. You’ve got to all be in it together. We drew money according to need, but it was all tallied up. One day it would level out. There was a rule of equality. No subsidising individuals. We were trying to pull something off together.

So yes, there were four mouths to feed, but also four people in different rooms meeting different people and different personalities working in different ways. That proved to be a success, but it was never guaranteed.

We never designed buildings together. One person always led a project. Others could review it, challenge it, engage with it, but someone had responsibility. We always feared that total collaboration would lead to compromise.

One of our rules was that if everyone likes what you are doing, it may not be very good. Discomfort can be a sign that something interesting is happening.

On how four founders avoided tearing each other apart…

When we worked together, we each had an individual building but in a collective city space and place. We never designed buildings together. Someone always had the lead on a project.

Professionally and publish wise, it’s owned by the firm. You don’t say by X of AHMM. Any AHMM building is by AHMM. But internally, someone was responsible for that. You could design review it, you could talk about it, you could engage with it, but they made the ultimate decisions.

We always feared a collaboration dragging everyone down to the lowest common denominator. So the golden rule was, if everyone likes what you’re doing it may not be very good. People being a bit uncomfortable, you might be pushing one thing or another, is actually a good thing.

The individual should own it, but for the collective wellbeing, just like the financial thing, the architectural thing is, it’s not a building by me or Paul, it’s a building by AHMM. And obviously increasingly by people within AHMM working under our studio umbrella.

It’s a competition but not a negative competition. We’re not competing for the same job. We’re competing to learn from each other to do things better.

On roles, strengths and who gravitated where…

Peter Morris was always a strategist and I think I suggested he did a course at Cranfield and he did an MBA in running an architect studio. That was his introduction to being MD.

Jonathan Hall, he always had a very particular kind of science, physics, maths brain. Quite a literary person too. His wife is an architect who became a construction law barrister. He had a natural understanding. Even now if you go to see lawyers he’ll say, well I was thinking shouldn’t we think about the bit, and I can see them thinking, Christ, he knows his stuff. He doesn’t tell people what to do but by God he knows his stuff.

Naturally they gravitated to places where they could best help the making of architecture. We have a saying about everyone, whether you’re a receptionist, document manager, librarian, you’re helping to make architecture. That is the fundamental reason why you might enjoy being there for the time you’re there, you’re helping to make architecture.

Therefore when a building is completed we do building tours. Lots of people from the office go, not just the architects, because it’s a collective endeavour.

On the business of architecture and why general practice mattered…

We were always interested in general practice. When we gave a Young Lions lecture at the RIBA, we joked that specialisation was, everyone said you must be a specialist. It’s still like that in America.

Our view was, we’ve studied for five years, we’ve done two years of professional exams, and then we’re narrowing ourselves down to one field. Actually if you think architecture is worth doing it should be done at all scales in all kinds of places.

David Dunster had always talked about Aldo Rossi and the background buildings of the city. The early stage of our career was focused on foreground buildings, great public institutions, and we were always saying, architecture must exist in all situations, almost like a social activity.

We never tied ourselves down to a particular field. We always thought our expertise was to make buildings and solve complex problems, make the complex legible.

Because we’d struggled so much, we were always having to talk about money to survive. With hindsight, that was a brilliant lesson. Opening in a good time is not necessarily a good thing because you think the gravy train will always carry on. Opening in a bad time can be wearing but it teaches you.

I don’t think we teach people enough about architecture as the broadest possible discipline. Architecture is about communicating with people, understanding place, understanding the moment in time, understanding the limits of the opportunity as well as the extent of the ambitions you can have.

Even to this day the profession will moan about money and fees and not being properly looked after. My point is, it’s our own fault. We are trained to love architecture. We are preconditioned to think great architects don’t make any money and all this stuff, and therefore it’s a self fulfilling prophecy.

It’s not a very generous prophecy because your life without adequate cash and continuous debt is quite miserable. And as a profession, who’s going to be attracted into a profession that doesn’t look after its people properly.

On local authorities and reinventing the profession…

Historically architects worked in local authorities. Thatcher broke up the local authorities, but when we were young architects there were not practices, it was almost a new thing, because most people went into local authorities and then some went into the famous practices that won the famous jobs, of which there were probably a dozen.

Local authorities were very successful and important practices. Park Hill in Sheffield, that was done by a local authority practice. But that model had gone. So we were at the cusp of the moment where people were reinventing the profession.

There was this dreadful term, a gentleman’s profession, which obviously meant you had a private income and you could cross subsidise. That was once deemed to give you artistic integrity. I think it now suggests a slightly closed profession, which I don’t think architecture should be.

If it is a profession that doesn’t generate wealth for people it’s not going to attract the right kind of people into it. The problem lingers on. It’s probably as difficult now as it has been, but at least the mindset is changing. People want to be looked after properly.

On happenstance, strategy and making the complex legible…

All projects come to you through happenstance in a sense because you never know which projects you’ll win and which ones of those you win will actually happen, and of those that happen which one will have that magic mix of opportunity and the zeitgeist to make it stand out.

The strategy was always, we are skilled at solving complex problems and making the complex legible and finding the real opportunity within the project to make something transformative at all kinds of scales.

Whether it’s finding a space for a desk in section in a tiny flat or cutting a hole in a huge building in Amsterdam to release part of the city that was disconnected.

We’ve always been interested in the primary strategic opportunity that intelligent design could solve. Then architecture is the ability to detail, deliver, and make that somehow delightful at a human scale.

Projects learn from each other. Architecture is a creative journey. If I’m building in the City of London it’s different to Amsterdam or Sheffield. If I’m building in a suburb rather than a town centre, if I’m surrounded by historical buildings rather than contemporary context, the client is an influence, the budget is an influence.

The underlying ideas are constantly evolving, but the appearance, we wanted it always to be a journey. I’ve looked at the idea of wrapping a building, now I’m going to look at expressing a frame, as an exploration of architecture’s potential related to the place, the time and the opportunity.

Looking to hire top talent

or advance your career? Let's talk.

or advance your career? Let's talk.

We connect exceptional firms with talented professionals.

Let’s discuss how we can help you achieve your goals. Get in touch with the team today.

Related Posts

Looking for insights into architecture salaries and design salaries in 2024? Our CEO and founder, Lindsay Urquhart, shares her thoughts on the global architecture and design market for 2024, and what to expect as the year unfolds.

We spoke to Nimi about how her personal and professional journeys inform her work and outlook. A must-read for anyone curious about architecture’s human side.

Angela Dapper on gender equity, landmark projects, and starting a socially focused studio – bringing big-practice skills to small community projects and finding rooms where people want to listen.