Simon Bayliss on Architecture’s Identity Crisis, the Modern Workplace, and Staying Hungry

What does it take to become a successful architect? How do you build an award winning practice culture? How do we fix the housing crisis? And are architects still hungry enough to make a difference?

In this episode, Simon Bayliss, Managing Partner at HTA Design, shares what he’s learned from 25 years at one of the UK’s leading housing-focused practices.

Why architecture?

Going all the way back, it’s usually common to start with Lego. We all had Lego growing up in the 70s and the 80s. There were a lot fewer choices of things to do. We didn’t have a telly, but we had lots and lots of Lego. I grew up near a farm. My grandparents were farmers and the buildings always fascinated me. A lot of this comes with the benefit of hindsight. You remember memories and look back and think, “Oh gosh, maybe that was important after all.”

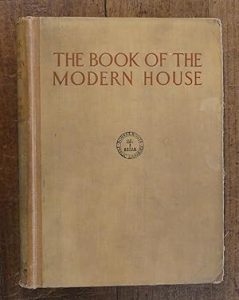

But probably, if I can track it back to a pivotal moment when I thought this is what I’m going to do, it must have been when a friend of my grandparents, who was an architect, gave me a book called The Book of the Modern House. I’ve still got it. It’s a first edition with a foreword by Abercrombie. It’s effectively chapters on classic English houses through to modernist ones, including a Lubetkin plan.

So if there was a moment, it was possibly holding that book. Alongside it was a copy of Architecture International magazine. It had the trio: Rogers’ Lloyd’s building, Foster’s Hong Kong Shanghai Bank, and something by Stirling. Together, that brought the old and the inspirational future high-tech vision of what the world could be.

With hindsight, I’ve gone into a housing world, so the leatherbound hardback first edition was probably more influential than the glossy magazine.

That was possibly the moment. There have been moments along the way when I’ve thought, “Is this for me?” and I’ve always turned around and thought, “Yes, it is.” I’ve stuck there. Every day I wake up and think, “That was a good choice.” I’m pleased with that choice.

It’s probably been very different to expectations, such as I had any, but it’s a fantastic career. I’m enjoying it hugely.

Simon working on his Grandparents farm. 1982

On the value of architects…

At the moment, I think the profession is wrestling with its fall away in perceived value. I think there has been an erosion of the value of architecture, particularly in housing where I work. The prevalence of design and build taken to its nth degree, has almost sidelined the design team completely.

That has led to a real problem in the industry. Grenfell might be the symbol of that, but there are lots of other examples of how construction and development have suffered through the sidelining of design professionals. Not just architects, but the architect as leader of the design team has probably diminished the most.

There’s a big discussion now, perhaps an existential crisis, maybe that’s too grand, about how we regain that value. We still offer it. But how do we demonstrate it more clearly? How do we regain some pride in what we do?

Day to day, doing the job, we add value all over the place. And in doing so, we add value to our self-worth.

Going to work every day, running a practice even in difficult times, overseeing projects, sitting through design reviews, being in the profession, it’s exciting. In London especially.

I grew up in the Lake District. There was architecture and interesting buildings, but nothing like I get to experience here. That variety every day is where the value comes for me. Even though we as a practice are focused on a single sector, we’re broad in design disciplines, locations and typologies.

That variety is the greatest joy in the work. One day you’re sketching, one day you’re on site, one day you’re in meetings… there’s a huge amount of different experiences. Whatever position you’re in, whatever point in your career.

Although, you have to work to get to that point. I did all the reflected ceiling plans for Ronald Reagan Airport in Washington when I was working over there. You think, “Is this really what it’s all about?” Of course it’s not. But as with any career that’s worth its salt, you have to do the hard yards. You have to get through the drudgery and understand its importance.

Technology has helped alleviate some of that, but only a little. There’s still a lot you have to do.

On joining HTA Design, and going from Part II to Managing Partner…

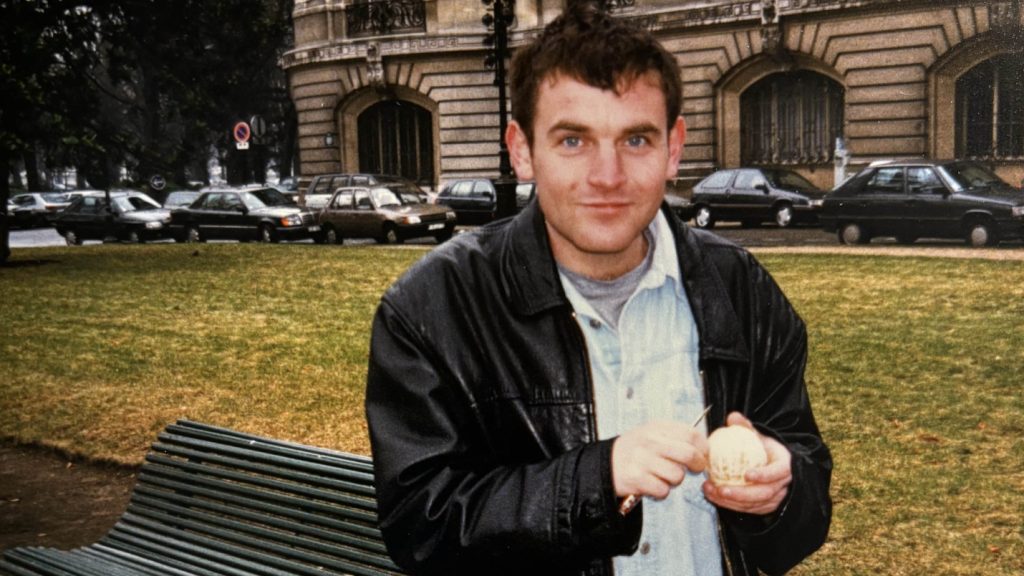

Simon in Paris, 1998 – around the time he joined HTA Design (then Hunt Thompson).

Was it a plan? No. I didn’t go in thinking this is my moment. I was doing a diploma in architecture and a joint diploma in urban design with a sustainability focus around housing at Oxford Brookes. This was 1998. I joined Hunt Thompson, as it was then.

They had just won the Greenwich Millennium Village competition, which was launched by the Labour government and sponsored by John Prescott. They won it in collaboration with Ralph Erskine at a time when collaboration wasn’t really a thing. It’s everywhere now, but they were early pioneers of that idea. Possibly because they thought they needed somebody like Ralph Erskine to give them the credibility to win.

But they beat everybody. Foster, Rogers, Zaha, Hopkins, Grimshaw, all the big practices of the day. So it was quite exciting. What they were proposing around housing, urban design, placemaking, and flexibility was all really fascinating. I’d been studying that in a very abstract way at university.

Then an advert came out in the February edition of the Architects’ Journal. I applied and got the job. I’ve still got the letter.

I joined a practice I was genuinely fascinated by. That’s a pretty good start. I was aligned with what they were interested in. But I also joined at a time of change. A group of us joined around that time, within two or three years of each other. Some joined within weeks. I still work closely with many of them.

We all shared a similar vision. Even though we were junior, we had a shared voice. We worked well together. And those are the partners who are mostly still there today: our head of communications, our head of landscape, most of the partners.

So when the time came for the practice to move forward, it felt natural that we stepped up. We were hungry for it. We were itching for it. When we took over in 2013, we did a management buyout. I had a head for numbers and ran the financial side. We just took it from there. It felt like a new chapter.

I’ve worked for the same practice for 26 years or so, but it’s seen a number of different iterations. The key thing is I’ve worked with the same group of people. And that is a complete joy. That’s a luxury. If you can find that, why would you move?

When you have a shared approach to your professional career and the culture of the organisation you want to create, it’s very difficult to walk away from that. I suppose I got lucky. Some people move because they’re looking for that perfect fit.

But it hasn’t all been easy. There have been moments when we’ve had to work quite hard to keep it all going.

On the shared vision of the partners…

The risk we have is that we’re sometimes a bit too aligned. We’ve got a number of sayings. If you spend that much time together, you start to develop catchphrases like you’re quoting films. One of those is, ‘leaning out the other way’.

When we’re all too aligned on an idea, a vision, a cultural point, or even a design, someone will say that. It keeps us balanced. Looking back, we’ve done quite well to navigate the last decade in practice, 12 years now as HTA Design.

So now we’re asking ourselves: how do we do the next decade? The first decade was actually easy, with hindsight. The last couple of years have been tougher. We have to look forward with positivity. There’s a great decade ahead, but we’re going to have to make it happen. It’s not going to fall into place.

That’s where we are now: looking outside, soul searching, leaning out the other way.

On building an award-winning workplace culture…

HTA Design has won the AJ100 Employer of the Year Award four times. This award is judged and presented by Lucy Cahill of Bespoke Careers London. In 2025, HTA won the AJ100 ‘Practice of the Year Award’, one of the most prestigious awards in the UK architecture industry.

HTA Design at the AJ100 2024

I guess it’s not about how do you manage to do it. It’s more like, how do you manage not to. Some of it probably comes back to luck, we all got on quite well. We’re a sociable bunch. Even now, the partners have an annual get-together with partners and kids. We’ve mostly been to each other’s weddings. Some of us are godparents to each other’s children. So there’s a social thread.

That was part of the culture even before we took over. When I joined, they served lunch every day. We all put on a lot of weight, and we went to the pub a lot as well.

On the other side, the practice didn’t necessarily do a good job of being a good employer in other ways. So when we took over, we thought if we’re going to spend all this time together, let’s make it a great place to work.

We wanted to be known for making great places to live. But we thought if we’re going to do difficult things like that, let’s have fun while we’re doing it. That became the mission: be good designers and be a good place to work.

It grew from there. We focused on paying people well, offering good benefits, especially ones that are cost-effective for us as a group, but expensive for individuals to do on their own.

We enjoyed being in good premises, so that became a priority too. The lunch thing came from the fact that when the practice moved to Camden Town, there was nowhere to get lunch. So they went around the corner to one of the partner’s houses. That grew into a tradition.

Every now and again we ask, “Are we too big now? Do we need to stop lunch?” During the financial crisis, we wondered the same thing. But the answer was always, “If we can’t manage to serve lunch, we should just stop being in business.”

It’s now part of the studio design. It’s where we do design reviews, hold evening events, it adds to the culture.

Along the way, other things became a focus. Our approach to EDI. My wife is an HR manager, she’s very focused on it, and we talk about it at home. My family is mixed race. So we talk about these issues in our daily life.

I’m not sure we consciously set out to be the best employer. We just tried to do the right thing.

Now the future is about rebalancing. You still have to be a high-performing organisation. It’s not all soft edges. It’s hard work. You still have to get the work done. You have to be talented and committed. That doesn’t disappear.

Keeping the balance right and the culture healthy comes from the top. The AJ have said that about HTA, it clearly comes from the partner team. Yes, we’ve got a great HR and studio practice team that brings ideas, but it’s not outsourced. That won’t go away. It’ll continue to evolve, but the intent is embedded.

On hybrid and flexible working…

It’s quite a challenge at the moment. The market has been very difficult. One reaction is to make everything run as efficiently as possible, and that often means wanting everyone in.

But that risks undoing some of the gains we’ve had since Covid. The idea that you have to be at your desk at nine o’clock feels absurd now. I remember running from the nursery to the station to make it in time. Some organisations may be going back to that, but flexibility is worth its weight in gold.

At the same time, what we do benefits from being together. We’ve created beautiful office space in London and in other studios. So how do you encourage people to come in when they need to? We’re wrestling with that.

I don’t think we’ve got the balance right yet. The general market is definitely shifting back toward four or five days a week.

I worry a bit about the loss of those formative years in the studio. Being around passionate designers and business people. Losing 40 percent of that time if people are remote two days a week is significant.

There are other benefits that might replace it, but overall, we design cities and places. If we’re not moving through them, we lose something. We could stay in our bedrooms and see the whole of the moon, but…

There’s a generational shift. Younger people are attracted to flexibility, but we know the value of being in the office. You learn by osmosis. You overhear conversations. You sit with a pencil next to a talented designer.

Office culture has changed. I arrived just after they banned smoking in offices. When we renovated our office, we talked about those booths where you take calls. We’d been in a temporary studio that was too small and hot. Those booths were awful.

So we thought, let’s not have those. But the studio is noisy. Back in the day, everyone was on the phone all the time, shouting at contractors mostly.

We tried to acoustically soften the space, and we bought good-quality headphones and mics for everyone. Now people take calls at their desks. And the people around them pick up what’s being said. That’s a huge learning benefit.

Mandatory five days a week won’t be part of our future. I’ve said that now, I might regret it, but I can’t see it.

Even before Covid, we worked across multiple studios. We put the best person on the project, regardless of location. Some of our studios, like Manchester and Bristol, were formed because senior people left London and we didn’t want to lose them.

We said, “Why don’t you set up there?” Now there are 15 to 20 people in each of those studios, plus Edinburgh.

On the multidisciplinary approach…

It’s interesting. Things often start for a particular reason, but the narrative shifts as you go on. We started as an architecture practice: HTA Architects. That’s what we did. Architects probably saw themselves as able to do everything. They even looked after cost. That’s probably a strength we should relearn – being able to manage cost and manage projects generally.

We had a project with a large landscape element. The architects naturally moved toward it, then realised they had no idea about planting. Everything is getting more specialist, more expert, more regulated.

Twenty-two years ago we brought in James Lord, a landscape architect, who’s since built a team of nearly 50 landscape architects. They do incredible work.

We’ve also got a sustainability team, a building physics team, and an interiors team. The interiors team came because a client said, “It would be useful if you had one, so we didn’t have to hire someone else.”

Some clients love being able to come to our studio and talk across projects with every discipline, including planning, communications, and wayfinding. Others prefer separate specialists. Both approaches work.

Before the buyout, the business structure created silos. There was separation. We removed that, mostly by getting rid of profit centres. We still report on figures, but it’s more collaborative now. We review each other’s projects even if we’re not formally appointed. That adds richness to the work and to the experience of running the business.

On housing…

We’re always looking ahead. In build-to-rent, we were ahead of the curve. We went to the US around 2010 to study how they were doing it. When UK clients like Greystar came in, we’d already done the homework. That gave us an edge. We’ve worked with Greystar and others for years now.

Co-living came from that. Clients in the rental sector had sites that didn’t work for build-to-rent. They’d ask, “What else can we do?” Co-living was the answer. It bridges the gap between student housing and conventional apartments. We’d already done a lot of student housing. Co-living is great for tight urban sites.

But we didn’t just jump in. We did deep research. We looked at global projects. We analysed metrics: studio sizes, amenity space, layouts. That research helped inform GLA policy. Our project was the first approved through that policy.

So it’s never entirely accidental. Sometimes it’s evolution, responding to repeated work with clients.

The city has changed. Many cities were hollowed out in the past. I remember going to Chicago 15 years apart. The difference was huge. Central Chicago became a place to live.

London hasn’t suffered in the same way, but the benefits of high-density urban living are clear. If that involves some height, I’m fine with that. I’ve lived in a tall building. It was fantastic. What matters is bringing green space and amenities with it.

On co-living…

When it’s done well, it works brilliantly. London is doing a good job. We’re seeing it expand to Manchester and Birmingham, but London is still ahead. Some of the operating examples here are excellent. I remember when we first got into it, a journalist said, “Rabbit hutches in the sky.”

But when I moved to London, I rented a room in a house with strangers. You get 10 square metres, a shared bathroom, and not much else, for a lot of money. Co-living offers a 20-square-metre studio, your own bathroom, a kitchenette, and shared space. You can meet people without sharing toothpaste. It’s a great offer.

Even on pure space metrics, it holds up. A standard two-bed four-person flat is around 70 square metres. That’s 17.5 per person. In co-living, you get 20 or more to yourself plus thousands of shared space. Some people don’t want a lot of space. They’d rather spend less, have a serviced, safe environment, because their lives involve work, travel, and socialising.

In the UK, we’re rigid. Our regulations and guidance quickly become mandatory. That can stifle innovation.

We’ve been working in other cities, giving modular advice, and we see similar constraints. Everyone’s pushing against the same rules.

Sometimes we have to ask: which rules are worth bending? There’s a generational element too. People are using space differently.

On the next generation of architects…

Every generation thinks the next one is lucky. They don’t have the downsides we had. But they’ll have their own.

We grew up under the Cold War. That felt real. Every generation has its fears. But overall, the workplace today is far better than it was a generation ago. Employment practices have improved. Choice and opportunity have improved. But hunger… that might have diminished.

I hesitate to say that, because everyone is different. But when I moved to London, I was just hungry. I wanted to learn, to achieve, to progress. And I felt the only way to do that was to work all the time. There wasn’t much else to do. So we worked. Then we went to the pub. Then we went back to work.

We probably didn’t get the balance right then, but we made fast progress. And I’ve always remembered that. Every time I was offered an opportunity, I took it. I ran projects. I did a listed building in Baker Street. I flew to Gibraltar, Dundee, Aberdeen. I worked constantly but I loved it.

I recently gave a talk at the London School of Architecture. My reflection was that architecture is the best career. There is no better career. Providing you’re prepared to work really hard. If you’re not hungry enough to work all the time, there are better things to do. Easier things. Possibly more financially rewarding things.

But all my friends in other fields also work hard. Maybe that’s the point. It’s not about architecture. It’s about work. And then I reflect: what else is there? Yoga on a Friday? Walking the dog? Those are more fun after a great week of work.

I do lots of other things, but I never forgot how to keep working.

On building trust and demanding a lot…

If that trust ever breaks down, if everyone starts saying, “We don’t trust people to work from home”, then you go back to 9 to 5:30, and we lose all the progress.

Some of the best changes came by accident through Covid, but they’re real benefits, and we should build on them.

You have to trust your staff. You already do. They have access to all your information. If trust is breached, it feels awful, but it rarely happens. People are generally trustworthy. They want to do the right thing.

Someone working from home might not do much, but plenty of people come into the office and don’t do much either. If you’re rigid and don’t allow flexibility, and someone doesn’t feel safe telling you that their kid is sick and they need to work from home, you’ll lose them.

You’ve got to trust people. They trust you to look after them. You have to trust them to look after you. If someone breaks that trust and doesn’t do their job, deal with it individually. Don’t punish everyone.

So yes, trust everybody. But demand a lot. You can’t make progress without high standards. But that doesn’t mean working 16-hour days just to show face. It means producing great work, showing commitment, being curious.

On whether the hunger has diminished…

It’s interesting with AI. It’s meant to be this big opportunity. And we are using it in the practice in lots of ways. But the exploration is mostly being done by more senior people. People who know what problem they’re trying to solve.

When I was younger, it was the juniors bringing in SketchUp and trying new tools. Have we lost that? Has the hunger shifted? Maybe. Maybe it’s a cultural rebalancing we need to work on.

On whether his career turned out as he imagined…

The job I do now isn’t that different from what I might have imagined 25 years ago. But I don’t think I expected to be doing this job. Part of that is I’ve never looked too far ahead. I’ve had ambitions, sure, but not fixed destinations.

The real difference has been the people. Being surrounded by like-minded people early in my career: people who stuck around, gave us momentum. We’ve achieved more together than we would have individually.

I’ve always been motivated, always been willing to work hard.

We went on a trip to Sydney recently. I was with Sandy Morrison, our head of design. He said it was the best work trip he’d been on because we worked constantly. And when we weren’t working, we were probably having a drink.

That combination of the social and the professional, just keeping at it, refining, improving, being open to possibility. That’s what has kept us moving forward.

In our 12 years since the buyout, we’ve become more open-minded. More aware of what’s possible.

On the housing crisis…

Housing was our choice. It’s what we care about. And it just happens to be the global problem to solve.

Tools like AI, off-site construction, they’re all part of the solution. The cost-of-living crisis is actually a housing crisis. Because if we weren’t paying so much for housing, we’d be wealthier, healthier, and more resilient.

People are spending half their income on housing when a third is the recommended maximum. That squeezes everything else: food, medicine, energy.

On what’s next…

If we’re in a state of permanent crisis, we need permanent solutions. We’re travelling more now, offering advice on off-site construction, modular systems. We’ve got expertise that can help.

The UK actually has a strong reputation for advanced housing delivery. We designed the tallest modular building in the world, it’s in Croydon would you believe? That’s exportable knowledge. Other countries are trying to do it. We can help them get there faster. We’ll keep developing our housing expertise.

Refurbishment and retrofit is going to grow. It’s been part of our past, and it needs to be part of our future. Many office buildings will become obsolete due to energy standards. They’ll need to be turned into housing.

We’ve just done a refurbishment of a mansion block where we inserted over 100 ground-source heat pumps. It now runs clean and, soon, cost-effectively.

There’s so much potential. So little time.

Looking to hire top talent

or advance your career? Let's talk.

or advance your career? Let's talk.

We connect exceptional firms with talented professionals.

Let’s discuss how we can help you achieve your goals. Get in touch with the team today.

Related Posts

Bespoke Careers has officially established a presence in the Washington D.C. market, appointing Lauren Cavanagh as the dedicated consultant for the region.