Why Are Architects Losing Their Influence? (And How to Regain It) – Chris Williamson

RIBA President Chris Williamson reflects on discovering the profession, building a practice, and how to regain architecture's influence.

On 1 January 2026, Chris Williamson took a deliberate and provocative step. He allowed his registration with the Architects Registration Board to lapse, describing the framework as ‘absurd’.

In practical terms, the sitting President of the RIBA, a practitioner with more than forty years’ experience and the founder of one of the UK’s most successful practices, can no longer legally call himself an architect.

“Since I was 18 it’s all I’ve ever wanted to do. But to be asked to pay an annual fee (which is increasing each year) to the ARB for the title – when the function isn’t regulated seems madness.”

This conversation was filmed in the weeks leading up to that announcement. It captures Chris at a moment of conviction, before he went public with a decision that challenges how the UK regulates the built environment.

As a working class kid, Chris was told architecture wasn’t for “the likes of him.” Decades later, as RIBA President and co-founder of Weston Williamson + Partners, he’s reshaped global cities through transport and infrastructure.

If you are interested in how architecture survives the collision of technological shift, class barriers, commercial pressure, and declining influence – this is for you.

On the moment architecture clicked…

There was very definitely a moment. I was studying at school and one wet Wednesday afternoon I picked up a book in the school library called Your Architect. It was an RIBA publication and all the illustrations in it were by David Rock, who sadly died last week. It described everything to me that I wanted to be. It described the profession and how you had a duty of care to the community as well as to the people that paid you. It talked about social values and what the whole role of the architect is.

At that time I had a place at Leicester Poly to study graphic design and I went to see my careers officer and said why has nobody talked to me about being an architect, this is everything I want to do. He said, well architecture isn’t for the likes of you. It’s a profession and the professions aren’t for working class kids. That’s something I’m passionate about trying to change, getting more diversity into the profession.

I begged Leicester Poly to let me study architecture instead of graphic design. It’s the best single decision I’ve ever made. I’m still as passionate about it now as I was then.

On where that sense of purpose came from…

Family together at seaside

My dad died when I was three. He had been a lay preacher and I think my mum wanted me to follow in his footsteps. I grew up idolising him and if he’d have lived I’d have probably found out he was just as flawed as the rest of us, but he was this perfect human being. The local vicar was really disappointed when I said I was going to study architecture, but to me they’re very similar.

I believe that architecture is like a religion. It improves the emotional, intellectual, physical, spiritual health of all of us. Good design is what I’m passionate about and I’m evangelical about it.

Growing up, there wasn’t anything about architecture apart from my mum. She had to leave school at 14 in those days, but she was very interested in everything and made me look at things and took me on visits to see buildings and things. I just didn’t know that you could make a living doing that.

Chris as a child

On class and the barrier to professional entry…

We have lots of young kids come to our office from Tower Hamlets and Southwark and they have no idea that you can make a career doing the things that we do. They love the models. They love the drawings. But they haven’t been told that you can actually do this and that there is a route into the profession.

Getting more diversity into the profession and different routes into it is something I want to try and change because there’s loads of kids that would make fantastic architects, but it’s just not being suggested to them.

I don’t think that mindset has changed. We volunteered for the London School of Economics, they were doing a survey about the professions to look at how many people in our office came from non-professional backgrounds. The average is about 15 percent of architects. I thought we’d do much better than that, but we were exactly the same, spot on the average.

It takes a long time to change those things. It’s like gender equality. It takes too long. They’re big ships to turn. Things are getting better, but getting better very slowly, and there is more we can do to push it along.

On meeting Andrew and founding the practice…

Andrew Weston and Chris Williamson

It’s really strange looking back. Andrew and I were put into group projects purely in alphabetical order and we found that we had very similar views on architecture but very different skills.

This was the mid 70s and it was the first sort of global energy crisis when the oil producing countries banded together and put their prices up. That suddenly concentrated everybody’s minds about fossil fuels and we need to do something about it, and it’s just taken 50 years for us to realise. I’ve just come from the national emergency briefing with Mike Berners Lee and Chris Packham and it’s pretty desperate. Nobody thinks that we’re going to hit the 1.5 increase, keep the limit, by 2050. We’re a strange race. We know what we need to do, but at the moment we just aren’t doing it.

I won a competition for energy conservation in 1979 sponsored by Tarmac and Andrew won a more glamorous competition judged by Norman Foster for House of the Future. So when we started our practice in the mid 80s, that was our passion, but it’s very difficult to get clients to do anything other than what they have to.

Even with brilliant clients, unless they have to do it, unless their competition has to do it as well, you can’t put them at a commercial disadvantage by saying you need additional insulation or additional glazing, energy saving measures, because that puts them at commercial disadvantage. We’ve been fortunate to get lots of repeat business in transport and that’s kind of allowed us to concentrate on that aspect of sustainability.

On skill sets, business realities and learning to manage…

Talking about AHMM, I’m very envious of their practice. If you were drawing a map of what you need for a practice to be successful, they’ve got great designers, they’ve got great business people, and they’re great socially as well.

One of our first clients was a small advertising agency and we converted an old women’s prison for their design studio. He was friends with Deyan Sudjic and Deyan said, ‘they’re great designers but you wouldn’t want to go out to dinner with either of them.’ It’s meant I’ve had to do more of the business side because Andrew and Steve, who we were all at Leicester together, all they wanted to do was design.

Most architects don’t realise. It was a different era when Denys Lasdun was around, or even Michael Hopkins who I worked with. Their modus operandi was to do a great building, get it published, and then that would get them the next project. The commercial reality these days is you can’t afford to do that. You can’t go more than a few weeks without the next job. You’ve got to line the next job up.

That kind of business acumen and business skill set, which we don’t teach at universities, is as important as the design.

So I did a project management master’s degree at South Bank University as soon as we started the practice. If I hadn’t done that, I don’t think we would have won the Jubilee line project because there was such a lot of form filling and quality management stuff which I’d learned doing the MA. It was also good because I was the only architect, apart from Molly von Sternberg. There were lots of property developers and surveyors, and we did a few small projects with them.

It taught you what other people in the property industry are looking at in an architect. They want you to be a great designer, but they also want you to be a good manager, stick to deadlines, and make sure you’re on top of their concerns, not just the design. The customer satisfaction surveys at the RIBA say people are very satisfied with our design skills but less satisfied with our business skills.

I’m a big fan of the advertising industry. They have a creative team and they have an accounts team. The accounts team look after the client and make sure everything gets done on time, and that leaves the creative team to do the work. I think we ought to be doing more of that.

On why architects are losing influence…

Historically, we have a hang up from the master builder idea, but also the fact that most architects in England are one man bands or small practices. So we think we have to be generalists.

I think that’s why we’re losing quite a lot of influence. We ought to be stressing our specialisms more. Then we would have more influence with politicians and decision makers if we put the right people in front of them, people with specialisms in schools, hospitals, infrastructure, AI. At the moment they kind of think of us as architects that do a bit of everything.

It’s raising awareness in schools to make people want to be an architect in the first place, but it goes further than that. Even school kids’ parents don’t know what an architect does.

On specialism versus generalism in the work…

It was a bit of both. We’ve done lots of other projects. When we started we did lots of conversions, converting warehouses to design studios. We did a church hall that won a Civic Trust Award. We were fortunate to be selected in the 40 under 40 exhibition in 1985. At that time we hadn’t started a practice, but Michael Manser who was the president then encouraged us to start.

His wife was a journalist and she was very encouraging. She wrote an article in the RIBA Journal after we’d done a few projects. Then we got put on a few shortlists, which are fantastic. Even if you don’t win them, you at least think you’re going somewhere by having those opportunities.

That’s something I’d like to see the RIBA doing more of for young architects. The talent is there, but the opportunities don’t seem to be there. A lot of local authorities like Southwark want to encourage small practices but they have to team up with older established practices in order to get a break.

We eventually won a competition for an office building in the Port of Tilbury in 1989. We’d done all the working drawings but they decided to stop the project. So we did another competition, as we always did when we hadn’t got anything to do, which was for Venice Bus Station. Paolo Vitta, an Italian architect who had been brought over from Hong Kong to choose people for the Jubilee line, saw it and put us on the shortlist for London Bridge. Since then we’ve got a lot of repeat business for that kind of work.

We’ve also done other projects and won other competitions. We did a laboratory in Boston. There were 300 entries and we got down to the last five and won it and built it.

Infrastructure seems to have stuck, and also because of the sustainability aspects. We found we really liked those kinds of projects. There’s a logical, rational approach to them which we liked. But also when you look at how those projects shape the city, they really change the way people live. The Jubilee line transformed the whole of the East End of London.

Other cities around the world look at what London’s done in terms of improving public transport, getting people out of their cars, and making the city a better place. Most cities have exactly the same sorts of problems. It’s not the career I thought I was going to have. I thought I would do more cultural buildings, but it’s actually been fantastic.

When it comes to climate change, things are improving. When I look back at how far we’ve come with solar energy and wind energy, that’s fantastic, but we’re not doing it fast enough. I hope our work has made a little bit of difference.

In defence of competitions…

I’ve got a lot of criticism about my passion for competitions, but I love the deadline of a competition and I love the fact that you can design something that you wouldn’t have an opportunity to do.

I understand completely that some competitions take advantage of architects and ask them to do too much work and give their ideas away and then just dismiss them, and they might get used by somebody else. But if competitions are run properly and they don’t ask for too much work, then they’re great.

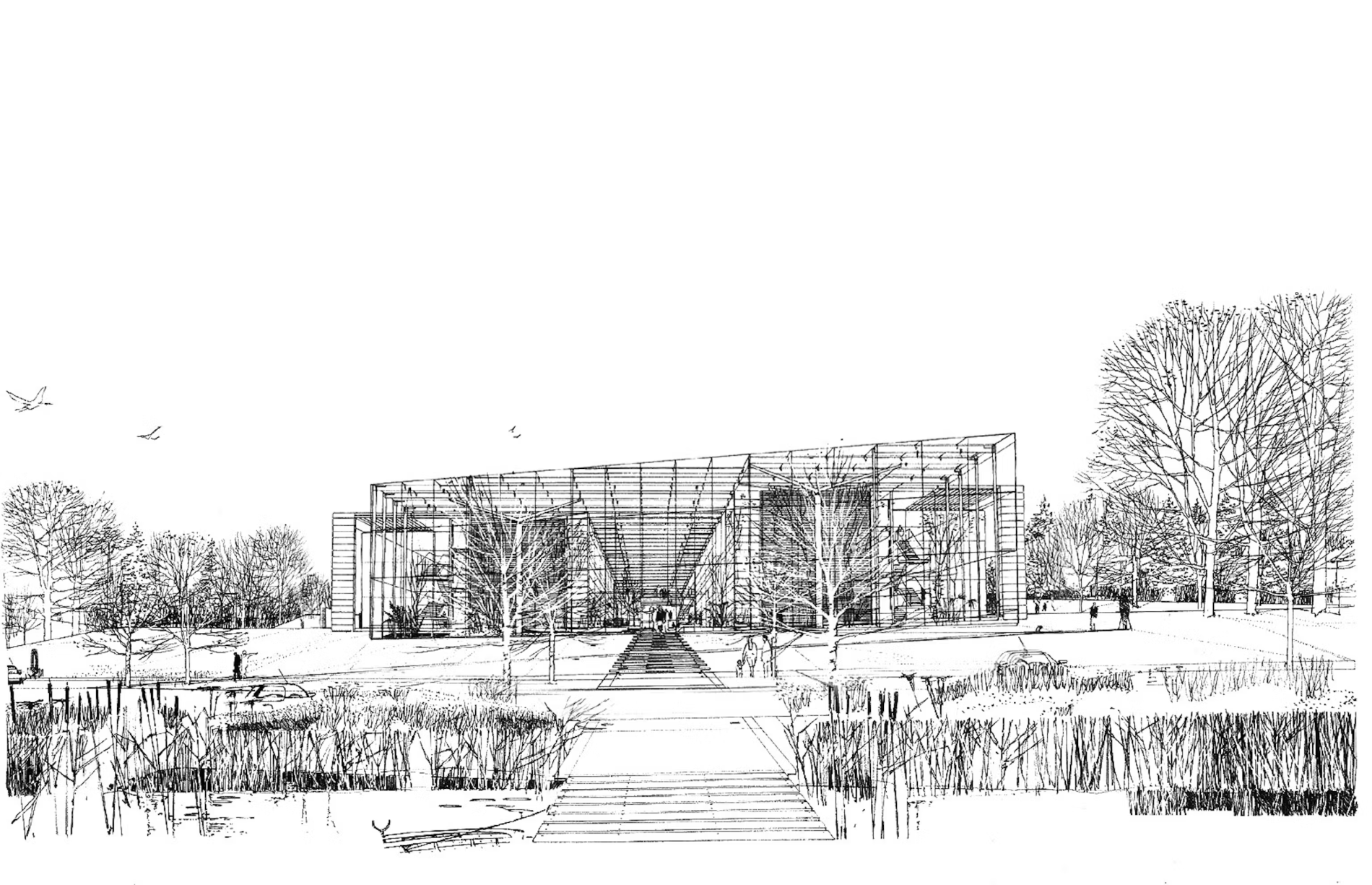

The New England Biolabs competition in Boston that we won, I spotted it and convinced Andrew and Steve to help me do it. We did it in a weekend because they said we’re looking for ideas and then we will pay you to develop the ideas. We came up with a really simple diagram.

New England Biolabs concept sketch

It’s really exciting to come up with an idea and submit it. In those days, the courier comes to the door and at that stage you’re convinced it’s going to win because it’s the best you can do. By the time the results come out, even if you haven’t won, you’ve moved on to something else. But it’s that opportunity to move your ideas forward.

I was in Miami at the World Architecture Festival last week presenting what was probably the smallest scheme there, a cycle route canopy which runs along the roads in Dubai to try and encourage cycling and walking as part of their 2040 vision. I’m still doing those sorts of competitions because I love them and it gets your ideas formulating.

Global Future Design Awards 20205. Gold Winner. Dubai Active Mobility

On partnerships, pressure and asking for help…

We’ve been really lucky with Andrew and Steve as partners. They’ve always had a desire for work life balance. As a small practice you can spend all your time working. They’ve always been sensible about making sure they had a home life.

That’s what we try and encourage in our office. People, you’re not just an architect. We’re all passionate about it, but sometimes you have to say to people, just go home.

There have been times that we’ve struggled for work, but we’ve been fortunate that people helped us. Terry Farrell gave us a competition to do in Västerås in Sweden for a railway station because he hadn’t got time to do it. We won it, but it didn’t go anywhere. Then he asked us to work on another project, a new town in Cambridge.

Dyson Davies asked us to work on their scheme for Swindon railway site master plan. Richard Horden saw that our competition entry for Grand Buildings was very similar to his. He got shortlisted, we didn’t, but he asked us to work on his competition entry.

That’s the one thing I would encourage young architects to do. We’re all so frightened about being turned down by phoning up and saying, look, can you help us. The worst that can happen is they say no. Architects are collegiate. They do like helping. We’ve done the same with people starting their practice having left us.

It’s still happening. Anybody that’s passionate about what they do is infectious about it. I mentor a few young architects. I go to lots of universities, degree shows, and there’s still the same passion and enthusiasm. You really want to help those people because you know they’re really good.

The profession’s changed enormously since we started. Everything was on a drawing board. It was only when we started doing the Jubilee line that we started doing CAD drawings. It’s revolutionised since then. That’s nothing compared to the speed of change now.

We’ve got a guy in our office who does the most amazing AI drawings and I’m always going in at the weekend and saying, how did you do that. They’re fantastic. They’re things that I can’t do. So you want to encourage them.

On AI and whether anyone can be an architect now…

At the moment, in my experience, it’s mainly being used in visualisation and putting forward ideas. Some of it isn’t very good at all. It pulls the wool over your eyes by having huge cantilevers which you can draw but you can’t build, but it looks so convincing that it’s actually quite dangerous. There are roofs being supported by glass walls.

At the moment you still need a properly trained person to interrogate it. That might change in the future.

The possibilities are in some ways frightening because anybody that can use the technology can be an architect. You could scan in your house and scan in lots of extensions from magazines and say, I like these, this is the kitchen that I like, and you’ve got 10 different alternatives at the push of a button. You can keep on interrogating it and it gets better and better and then all you need to do is find a builder to build it.

It can be frightening, but it’s up to us to keep adding something that technology can’t do, the empathy and the knowledge.

Every profession is going through the same thing. There’s a democratizing effect to some extent. The professions have changed in my lifetime. When Andrew and I were studying there was a published fee scale you had to charge. By the time we set up our practice that had changed and the fees have steadily dropped. It’s seen as anti-competitive to have a published fee scale or even a recommended fee scale. There’s good and bad about it. It’s mainly bad in terms of pay and fees, but there are a lot more opportunities because of it as well.

On handing over the practice to the next generation…

In some ways it’s frustrating. You know it’s going to happen at some time. I’ve been around long enough to see other practices fail to make the next generation. I think back at all those fantastic practices I used to look at and admire when I was studying that aren’t around anymore.

Engineers manage to hand over the practice more than architects do because there’s more creativity involved and more personality to the design aspect. It’s the same with an artist. You can’t hand over something as a sculptor or an artist or even a photographer or an architect. You can’t hand that over.

What you can hand over is a system and a reputation and a style, a way of doing things. You rely on the people that you choose to take it on and evolve it. It won’t be the same, but it’ll be different, and hopefully it’ll be just as good.

My 16 year old self would be amazed at what I’ve done, but by the same token, as you grow older, you get more ambitious. It is difficult to let go. I miss being involved in the day to day cut and thrust of all the projects around the office. But you have to realise the younger generation don’t want you interfering. They don’t want you saying, we did it like this, or I would do it like that. Things happen too quickly on projects. You have to learn to let go a bit.

On what you want your legacy to be…

There are certain things I can already see where there’s a different emphasis. I instigated a matrix of assessment for people so you didn’t just look at what they did, you looked at how they did it and their contribution to the office as well.

When it came to salary rises and bonuses, you would look at a range of things about how they dealt with their fellow workers, their contribution to the office, rather than just the work they did. I think that’s really important, and also important to have that broad skill set throughout the office.

There’s always a balance in the creative industries between the emphasis on design and the emphasis on the business. It’s a difficult balance to get right. But there isn’t one way of running a practice. Everybody does it differently.

I know what I like. I’ve always liked encouragement and involvement and a collegiate way of working. I’m reading Matthew Syed’s book about how it’s important to have diversity in the office, different voices, because if you don’t you can miss something completely.

I hope what stays the same is that young people are given a chance and involved and encouraged. It’s not just about your technical ability. When I’m interviewing people, I always look for energy and enthusiasm and excitement and passion, maybe at the expense of technical competence. But I tend to think if you’re passionate about something, you’ll learn those other skills.

When CAD first came in, we used to visit practices that just had CAD operators and then the design team. I don’t think that’s a very good way of splitting the office. If you’re passionate about something you’ll develop the skills.

On why you decided to run for RIBA President…

I’ve been concerned about the way the RIBA is losing its influence for some time. It’s not just architecture, all the professional institutes have to change. They were set up as learned societies. When I was young it was the place you went. It had all the best talks, lectures, exhibitions, competitions, awards, and one by one other people have started doing that, which is great, but we should be collaborating with those people if we’re not going to do it ourselves.

Our awards are actually the best because they’re visited and very thorough, but other people get more publicity doing it. I’ve judged awards where you get a bunch of photographs, some text, and you’re asked to decide. It’s completely false, but they’re highly regarded and they have gala dinners that make loads of money.

I think I have a particular approach to how to change our influence. The RIBA needs to be seen as more of a qualification and a set of excellence for lifelong learning, so you can say to your client and to decision makers, I’m better than that guy. When I was young it was an organisation you wanted to join because it was a brand you wanted to identify with. It marked you out.

I want us to get back to where we were, more political influence and greater respect in society.

The first thing I did was ring round other people that I thought might stand and ask if they were standing, because I didn’t want to stand against people I thought would do a great job.

It’s a strange situation because you have to go up and down the country telling people what you’re going to do in order to get elected, in the full knowledge that you haven’t got any power to do it. You’ve got to work with the executive and the staff to get things done. I’ve written a two year plan and that’s been accepted by council and by the board. That should be what we’re doing for the next two years.

I’m really excited about it. At this time in my career, I wanted to do it while I’ve still got the energy and enthusiasm. In five years time I might not have.

On the first stretch in the job…

There hasn’t been a moment where I thought it’s harder than I thought. The great thing is when you delve into the RIBA, you realise a lot of the things I’m passionate about and want to do, people are already working on, but you have no idea they’re working on it.

The only issue I’ve got is making sure things are done in an efficient time scale. In an architectural practice you have a meeting, agree what you’re going to do, and everybody goes away and does it. The larger the institute gets, the more difficult it is to get all the departments working together. That’s what I’ve got to try and do.

One of the key things is reorganising lifelong learning so people can create their own careers throughout their lifetime. At the moment we’re making everybody study the same thing essentially.

A knighted architect asked to see me because he was worried he was being interrogated about his CPD on fire life safety. In his position he doesn’t need to know certain measurements. He needs to know in his office who knows it. He needs to know it’s important. We shouldn’t be asking people to do the same thing.

I’d like to see us incorporate more specialisms into lifelong learning so you can concentrate on certain things. Most of my mailbag is full of complaints about low fees and low wages, but in order to do something about that, we have to get better and we have to let people specialise.

If you became an expert in sustainability or conservation or AI or management, you’d stand a chance of having a better salary or better fees by convincing your client you’re good at that. At the moment we can’t really do that with the way we’re doing CPD.

One of the first things I did was sit down with a map of the Labour cabinet and start putting names to a shadow cabinet for architecture. Against the housing minister, the health minister, people that know in depth their subject. In the past we haven’t been sending the right people to meetings. We need to do that nationally and locally and internationally.

We want to grow our international membership. When I was international vice president a few years ago, so many institutes, Brazil, Mexico, Korea, wanted to collaborate with us on lifelong learning. If we can get that right and deliver it online, we can grow a global community because a lot of the problems we have are global issues. We can work with them locally but raise the standard of the profession, not just here but elsewhere as well.

On why young architects aren’t joining the RIBA…

It’s not just architecture, it’s every profession. These societies were set up in a different era. There is still great relevance, but young people in our office don’t want to join something just for the sake of it. They don’t see the relevance. You can get the same information on your phone from lots of different places.

They are passionate about career development. They will do an MBA if they think it’s going to get them a better job or better opportunities.

That’s what I’d like to see us develop into, still as a learned society, but changing the emphasis so that those initials RIBA actually mean something. It doesn’t mean a membership club. It means you’re the best at something.

Then you can specialise and demonstrate your worth. You can go to another office and say, this is what I’ve been studying for the last year. These are my marks. You wouldn’t be competing with every other architect in the country.

I did a BREEAM assessment course last year so I could assess projects and act as a peer reviewer. I did about 120 hours and ironically I was only allowed to put down two hours in my CPD because I have to tick all the other boxes. That shows you how bizarre it is.

They should just be able to say, this is what I want to study and this is why I want to study it. That’s where I’d like to get to.

Those online courses are excellent because they take away the angst. That’s where I’d like to see Part 3 get to as well, because at the moment if you don’t pass Part 3 you’ve got to wait six months or a year to do it again. It’s so costly.

These courses are online, well organised, well assessed, mainly multiple choice, and if you don’t get them right you can go back and do them again. I find it a really good way of learning. It’s not just cramming for an exam and forgetting it as soon as you walk out the exam room.

If you can do it online, you can do it all over the world and make those modules available to people wherever they are that want to become a specialist or get that knowledge.

On protection of function versus title…

I think it’s bizarre that we’ve got protection of title but not protection of function. It’s completely the wrong way around. You don’t have to be an architect to design something. Yet we like to call ourselves architects and get really upset if other people call themselves architects that aren’t.

I would like to work towards protection of function. It is RIBA policy as well. Possibly not for every project, it depends on the size. There are capable architectural technologists that can do some things. But in terms of design, protection of function is something we should work towards, and that would be a great boost to the profession.

We’ve got to do something about procurement as well and make sure government understands they shouldn’t be accepting the lowest price. When you go out shopping for a car or a suit, you don’t go out saying I’m going to buy the cheapest thing I can find. You’re looking for value for money and good quality at a reasonable price.

We’ve got to get into a position of influence in order to do that and demonstrate that we know what we’re doing. Lifelong learning and political influence add up to getting to where we should be.

On what success as RIBA President looks like…

One of the things I’ve had to do so far is judge the Stirling Prize, which has been amazing, and phone up the person that’s won the Royal Gold Medal. We have to write a letter to the King to say this is our nomination, so we have to phone the person first to ask if they would accept it. That was really emotional.

I’d love to be able on the last day to look and think the profession is in a better state in terms of influencing government policy, and also the reputation.

I’d love to get more architects into schools. I’d love to get city architects in planning authorities, city champions, and that’s something we’re working on. The various campaigns about Level 7 apprentices, getting the funding for that, there’ll be lots of things I look back on.

In the nature of things I’ll have achieved some of them and not achieved others. It’ll be mixed emotions, things you’ve been able to do and things you haven’t. When you pick up any book on an architect’s life, it’s full of things that got built and were brilliant and things that didn’t go anywhere. You have to get used to that.

Looking to hire top talent

or advance your career? Let's talk.

or advance your career? Let's talk.

We connect exceptional firms with talented professionals.

Let’s discuss how we can help you achieve your goals. Get in touch with the team today.

Related Posts

Shawn Adams on making design public, cutting the jargon and opening the door for the next generation.

As we enter a New Year, the collective sentiment is to look forward, make plans and think about the future, me included. But as we do, it is hard to not reflect on the past year.

Bespoke Careers is proud to support this event celebrating people-focused achievements in architecture, highlighting sustainability, workplace culture, and fellowship.