Why I Never Became an Architect – Peter Murray

A conversation with the co founder of New London Architecture and the London Festival of Architecture on careers that bridge media, practice and city making.

Peter Murray once herded longhorn cattle down St Johns Street in London to make a point: Architecture should speak to everyone. In this conversation he unpacks a life spent shaping that dialogue from AA student to editor of Building Design and the RIBA Journal to co founding Blueprint, Wordsearch, the London Festival of Architecture and New London Architecture.

We get into why so much architectural writing misses the public, how to switch the language, and when he realised he was becoming institutionalised and needed a reset. He talks candidly about raising the game at BD, opening the debate beyond the profession, and building platforms that connect designers, policymakers and the public.

Why architecture…

I thought from a pretty young age that I wanted to be an architect because in those days that seemed the only way to be involved. I grew up in Lacock in Wiltshire, then classed as the most beautiful village in England, competing with nearby Castle Combe. I slept in a bedroom with a cruck beam over my head.

My father loved parish churches, so wherever we went we stopped to look at one. Lacock Abbey was a favourite a 14th century nunnery later extended in Strawberry Hill Gothic by Sanderson Miller. As a teenager I guided visitors there after the National Trust took over. Bath was close. I was immersed in historic architecture and heritage. Later I realised there were other ways to be involved than training and practicing.

On training and leaving practice…

I started at what was then the Royal West of England Academy School of Architecture in Bristol for three years, then went to the Architectural Association for fourth and fifth year. After my third year I interviewed with Patrick Hodgkinson who was working on the Foundling Estate in Bloomsbury with a ziggurat format. He offered me £8 a week, but a London flat was £10 even in summer.

Wiltshire County Council Architects Department paid £1 a week and my bus fare was 17 and six, so it was more profitable to stay. I had gone there for the prefabricated schools programme inspired by Hertfordshire, but by the time I arrived nothing had started. I spent time on sites and twiddled my thumbs. I had also thought about doing English because I enjoyed writing.

At Bristol I produced newsletters and a student magazine with Michael Dean and got involved with BASA, the British Architectural Students Association, which connected me to schools across the UK. Magazines became how I related to architecture alongside studio.

On paper architecture and thinking beyond building…

At Bristol my heroes were Peter Cook and Archigram. Cedric Price came to talk and that took me to another level in thinking about architecture versus practice. Cedric’s built work was minimal but his designs and his attitude to building and non building and planning and non planning were highly influential. He mentored me and my co editor on Clip Kit as long as we made an appointment. He introduced me to Reyner Banham who was writing for New Society and fascinated by Los Angeles, which I also wanted to explore.

BD vs the RIBA journal…

I was pulled between the consumer press and the trade press. I chose the trade press for the level of detail. I went to Architectural Design because people I respected wrote there Cedric, Peter Cook, and Bucky Fuller. I got to Building Design almost by accident. I wanted to go to California and wrote to magazines. BD replied. Mike Sharman asked me to interview Schindler’s wife in the Schindler House. I met others including a chap called Frank Gehry then in a small studio doing furniture. When I returned BD was looking for an editor.

BD called itself the magazine for the building team, but most readers were architects. It was seen as the Daily Mirror of the profession compared to the AJ. My job was to raise its seriousness and focus on what the profession was doing. Paul Finch was my news editor. We sometimes ran long nine point features to prove readers would engage. We were often critical of the RIBA. When I became editor of the RIBA Journal and managing director of RIBA Magazines I had to change tone. I still tried to give writers freedom and separated the practice section for institutional news and regulations from the rest. I worked closely with presidents Owen Luder and Michael Manser, managing PR week by week and sitting on policy. It was interesting but I began to feel institutionalised.

Starting Blueprint in the 80s…

Blueprint was a reaction. We had no money and the early 80s were dire for the profession. The Fosters and Farrell Grimshaws were doing okay, but the next generation was in paper architecture. We started Blueprint at weekends. I convened a lunch at Les Cargo. About half the 25 journalists agreed to work pro bono to test it. The AA’s print room became our makeshift production space. Simon Esterson created a strong identity. Deyan Sudjic came in as editor. He had learned to write for a broad audience at the Sunday Times. We worked Saturdays on news and laid out on Sundays until four on Monday morning, then I went to the RIBA.

We raised small sums from Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Terry Farrell, Terence Conran and Rodney Fitch, then later raised around £100,000 properly. We never had huge direct sales about 12,000 circulation but the content was picked up by other media, especially the BBC. It was the design decade and design became mainstream.

On Wordsearch and communicating to the market…

Wordsearch grew by chance. In the mid 80s the economy took off. Big Bang deregulated banking and the City needed buildings. Stuart Lipton read Blueprint and wanted collateral more like it. We started newsletters and brochures for Broadgate. Peter Palumbo called next. James Stirling’s Number One Poultry needed drawings clients could understand. Mike Stiff produced hand drawn perspectives. Ricky Burdett’s links to SOM brought competition books and more work. We were all in 26 Cramer Street alongside David Chipperfield and the 9H gallery. Work flooded in, so we set up a separate studio and used the Wordsearch name we had created for Blueprint’s company.

Then the crash hit in 1989. Piles of blueprints came back marked gone away as practices folded. Blueprint’s sales and ads dropped and we eventually sold it. Wordsearch was ironically saved by IRA bombs in 1992 and 1993. Damaged buildings needed repair and reletting and insurers paid for marketing. We ended up doing brochures for nearly half the City of London over 15 years, then expanded to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Abu Dhabi and later Singapore and Bangkok. I stayed involved until around 2010, increasingly part time after starting NLA in 2004.

Writing to sell vs writing for peers…

It was a completely different kind of communication. Some architects treated brochures for occupiers as if they carried a bad smell, but it is essential if you want your buildings occupied. Property agents hired us and our format became known as a word search brochure, which annoyed competitors. Stuart Lipton had invested in research into what the market wants, learning from Gerald Hines and hiring DEGW. Frank Duffy and John Worthington’s work on open plan and occupier needs was pivotal. We built brochures around what occupiers needed location, technical detail, imagery, specification and amenities. I studied luxury car brochures too. Rolls Royce was beautifully produced and very clear on what you were getting. Later the market became fluffier and less technical.

Starting the London Festival of Architecture and NLA…

Venice Biennale’s parties were wonderful but had little impact on Venice. I wondered what would happen if you embedded that energy in London. Tell people your idea and you are forced to do it. After an interview in the AJ I had to act. We raised funds. Alfie Buller in Clerkenwell gave £35,000 and many ideas. We found a brilliant empty warehouse next to what is now St John restaurant and used it free. Our first event marked St John Street’s historic cattle route to Smithfield. We laid grass on the street and drove longhorn cattle down it. They got frisky halfway and I thought what have I let myself into, but we penned them and around 15,000 people turned up. Animals were useful early on sheep across the Millennium Bridge in 2006. Norman Foster had agreed to be shepherd but pulled out two days before. Richard Rogers said yes and Renzo Piano joined him.

Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano herd 30 herdwick sheep across the Millennium Bridge.

In late 2004 Michael Rose, chair of the Building Centre, asked how to get people into the refurbished space. I said one exhibition would not do it. Do London and make it change. Nick Maceo from Pipers and I had worked on a City towers show and believed in the model as a public explainer. Trustees unanimously agreed. The night before we opened NLA London won the 2012 Olympics. The morning we opened a 7 July bus bombing shook Tavistock Square nearby.

What NLA is for…

The festival planted seeds that took years to grow. Greening St John Street is now on site. Pedestrianisation images for West Smithfield look like our festival scenes. NLA became a network across disciplines because the Building Centre felt like neutral ground. I remember chairing an infrastructure event and seeing engineers in anoraks alongside designers. Our agenda followed the London Plan. The first plan, shaped by Richard Rogers after the Urban Task Force, set a compact city approach transport oriented development and densification that enabled growth. We have not built enough housing but the framework worked. Now a new plan is coming post Brexit and post Covid with different economics and stronger sustainability. I worry City Hall lacks a Rogers scale vision for the next 30 years.

On London’s global standing and the English pragmatists…

London is on the map even though some leading figures built little here. David Chipperfield and Zaha Hadid did less in London than their reputations suggest. Rogers and Foster’s global work, like the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, promoted high tech. But the next generation, many trained with them, took a different line. I think of English pragmatists pragmatic, client focused, responsive. Practices like AHMM, BDP, Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands and many others deliver thoughtful buildings without a fixed stylistic brand, more responsive to context.

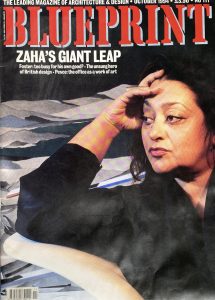

Peter with Zaha Hadid

London’s strength is multicultural. We built huge international studios with high quality output. Fewer new people arrive now after Brexit, but many stayed. London remains a centre for design and architecture because of language, law, time zones, Heathrow’s connectivity and the number of languages spoken. Engineers underpinned this Arup internationally, Buro Happold in the Middle East and others.

On my approach to making things happen…

Architecture is great training for many things. The holistic approach is unmatched. You have to cope with clients, occupiers, foundations, services and aesthetics and bring it together. Studio teaches projects with a beginning and an end. I learned business later on the job. In Bristol we had one lesson on practice management keep two years of money in the bank before starting up. In the 1970s architects could not approach clients, which meant work came through golf clubs and Rotary. I argued for marketing. Sending a brochure is more transparent. Communication has been central to everything. At IE University in Madrid I taught communications on an MA that joined the business school and architecture. The key is to think hard about who you are talking to. So many architects write as if talking only to other architects. At Blueprint Deyan taught us to use different language for a wider market so the person in the street understands and is interested.

Lessons and advice…

I did not imagine life at my age. I was a fan of The Who and the line hope I die before I get old. I certainly did not think enough about pensions. My approach was to see something that interested me and go for it. That goes back to projects. Someone sets a project and you work out how to do it. Architects should be proud of that breadth. When we named New London Architecture I argued for architecture not a wishy washy word like place. Architects have an important role in the world. The RIBA should help people respect architects, understand them and pay them properly. I am excited by city architects. With the right people architecture and planning backgrounds can deliver positive change. I am campaigning for that.

Looking to hire top talent

or advance your career? Let's talk.

or advance your career? Let's talk.

We connect exceptional firms with talented professionals.

Let’s discuss how we can help you achieve your goals. Get in touch with the team today.

Related Posts

Advice for moving countries as an architect or designer in 2026.

From studying at Yale to leading global megaprojects like Changi Airport and Hudson Yards, Forth shares what’s changed in the profession, why architecture is a service business, and how to lead without losing the joy in design.

Every employee has one thing in common: they’ve experienced the ‘interview.’ Whether you love them or hate them, they’re an essential part to any application process.